By:

- Michelle Brubaker

Published Date

By:

- Michelle Brubaker

Share This:

Michael Madani, MD, cardiothoracic surgeon at UC San Diego Health, performs a PTE procedure.

Give and Make

On January 8, 1968, the Evening Tribune reported that, “the field of human organ transplantation will arrive in San Diego with the opening of a transplant unit at County University Hospital.” Within a month, the community hospital, operated by UC San Diego, performed the region’s first kidney transplant on a 32-year-old aircraft worker.

Marshall Orloff, MD, then chair of the Department of Surgery, declared the transplant surgery to be a success, but warned many future patients would not fare as well. There would not be enough donor kidneys.

His prediction was right. In the following decades, thousands of patients nationally would not survive the wait list for a healthy donated organ.

Each day, 20 Americans die waiting for transplants of kidneys, livers, hearts and lungs. Someone new is added to a wait list every 10 minutes. More than 120,000 adults and children are currently on transplant wait lists. They are not getting shorter.

Since the launch of its organ transplant program 50 years ago, UC San Diego School of Medicine has been a leader not only in organ transplantation, but in developing surgical innovations to address the dire lack of organs available for implantation.

In the 1970s, UC San Diego developed what is today an internationally recognized surgical program to treat a deadly condition called chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH). The surgery is a highly specialized, life-saving procedure that returns failing hearts to normal function.

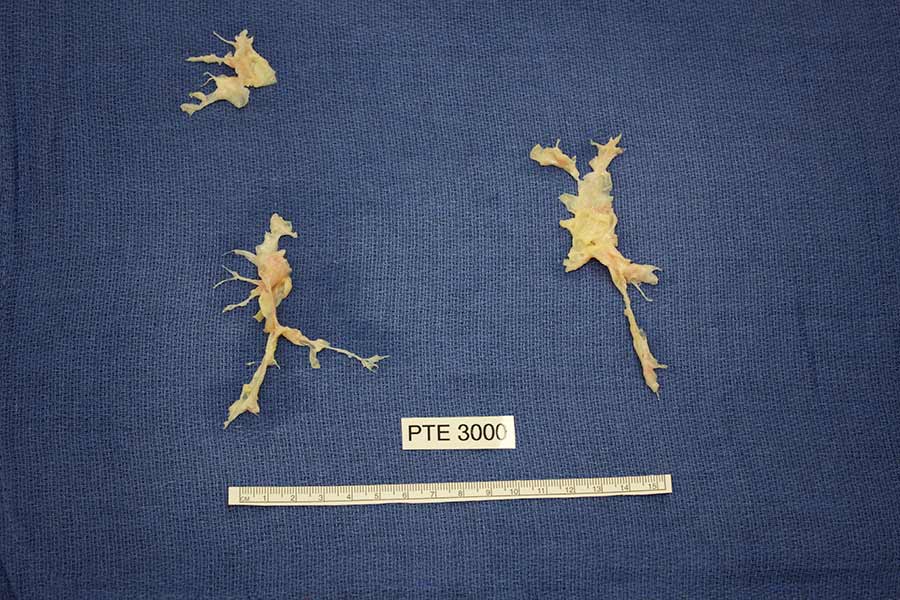

The pulmonary clots removed from Susan Geertsen, the 3,000th patient to have PTE performed at UC San Diego Health.

“Before pulmonary thromboendarterectomy (PTE), critical pulmonary issues were only treated with a heart and lung transplant,” said Stuart Jamieson, MB, Distinguished Professor of Surgery. “The surgery grew out of the necessity to find alternative ways to treat patients in the face of organ donor shortages.”

The PTE program was established at UC San Diego School of Medicine by Kenneth Moser, MD, pulmonologist, and Nina Starr Braunwald, MD, who was among the first female surgeons to perform open heart surgery.

“They set the groundwork for a truly innovative approach,” said Jamieson, who became director of the PTE program in the 1990’s. “Pulmonary hypertension from blood clots was not always looked at as a disease. Now, it’s recognized as a disease, and because of UC San Diego’s pursuits, one that can be cured.”

PTE is an open chest surgery, but in its early days, was performed through one side of the patient’s body, and only on one lung. Today, the patient’s body is cooled and the blood is completely drained. Brain activity is temporarily flat-lined. The bypass machine is stopped for 20 minutes while the surgeon races against the clock to remove blockages from each lung.

UC San Diego Health has performed more than 3,700 PTE procedures, more than any other institution in the world. Patients worldwide are referred for the procedure. Susan Geertsen, from Kansas, was the 3,000th patient to have PTE performed at UC San Diego Health three years ago. She noticed something was wrong when she lost her breath from walking down a flight of stairs.

“When I finally went to a pulmonologist, he told me I just needed confidence to breathe and to come back in three months,” said Geertsen. “I was not happy with that answer.” She was eventually referred for PTE at UC San Diego Health, which is a global model with the lowest mortality rate.

“It takes an incredible amount of focus to work with such tiny arteries. Every second and every movement counts,” said Michael Madani, MD, chief of cardiovascular surgery. “It truly takes a multi-disciplinary team to care for these patients and that’s why our hospital has a great success rate with this procedure.”

Madani has upped the PTE game and is using novel techniques from minimally invasive and robotic cardiac surgery. “We are tirelessly searching for new treatments and techniques to preserve our patients’ heart and lungs so that transplantation is not needed.”

Geertsen was breathing easier shortly after surgery. “My cheeks were pinker. My hands were not as dry. I can’t believe how much my body needed the oxygen,” said Geertsen. “I’m look forward to many years with my grandkids, playing in the park and going to the zoo.”

Two Lefts Make it Right

The first human heart transplant occurred in 1967, just a year before UC San Diego School of Medicine opened. The patient survived 18 days. In the years since, much has been learned. Heart transplants today are comparatively common and dramatically more successful. More than 2,000 occur in the U.S. annually. UC San Diego Health surgeons perform the procedure dozens of times each year.

But one problem persists: There aren’t enough donor organs. Nearly 4,000 persons are on the national heart transplant waiting list; some will die waiting.

Left ventricular assist devices, or LVADs, are small mechanical pumps implanted inside the left ventricle—one of the heart’s four chambers—to help the weakened organ pump blood. LVADs do not replace the heart, but they can mean the difference between life and death.

Amanda Gabaldon, heart transplant patient at UC San Diego Health, holds her newborn baby.

Patients like Amanda Gabaldon needed an LVAD to keep her alive until a heart transplant surgery. “I knew I had to fight for my daughter,” said Gabaldon, who was diagnosed with peripartum cardiomyopathy, a rare cardiac disorder, shortly after giving birth. “I am not a quitter and always strive for success. I wasn’t going to let heart failure beat me.”

Gabaldon was also the first patient at UC San Diego Health to receive the Boston Scientific Subcutaneous Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator (S-ICD), which monitors heart activity and shocks the heart when it goes into a dangerous rhythm, a function not performed by the LVAD.

“In the past, if someone had heart failure and their heart was not adequately supplying blood to tissues, they would have the option of getting a heart transplant or dying,” said Eric Adler, MD, a cardiologist and medical director of heart transplantation and mechanical circulatory support at UC San Diego Health. “Now, we have many advancements in technology to keep a patient alive until a new heart is available.”

LVADs aren’t new. The first successful implantation happened a year before the first heart transplant. The technology has improved, but more can be done. There is, for example, no FDA-approved, durable right ventricular assist device.

LVADs aren’t designed to function in the right ventricle, but in recent published research, UC San Diego Health surgeons have shown they can work, implanting the devices inside the right ventricles of three patients in dire need of right-sided circulatory support. The pioneering surgeries were successful; all of the patients subsequently received heart transplants.

Since then, Adler and colleagues have performed the procedure 11 times with a 100 percent 1-year survival rate. “There is no standard of care for patients with biventricular failure,” said Adler, “so using two LVADs to address this critical need gives patients another treatment option and hope.”

In 2011, UC San Diego performed the West Coast’s first implant of the world’s only FDA-approved total artificial heart. During the four-hour procedure, the patient’s diseased heart was completely removed and replaced by a device that rapidly restored blood flow to his entire body. Like LVADs, the device was a “bridge-to-transplant,” intended to sustain and improve a patient’s life until a donor organ became available.

UC San Diego Health’s transplantation programs do not stop at single organs. It’s a regional leader in multi-organ surgeries, performing combinations not offered in other hospitals, such as combined heart-lung, heart-kidney, lung-liver-pancreas, liver-pancreas-kidney and heart-lung-liver transplantations.

In 2016, UC San Diego surgeons successfully performed the region’s first heart-liver transplant. Less than 10 of these surgeries are done in the U.S. each year.

“I sincerely thank everyone at UC San Diego Health from the bottom of my new heart…and liver. I went in one door very sick and came back out a new person,” said Sonny Taitano, a father of six children and grandfather of thirteen. “I can breathe again. I can speak again and I am enjoying the simple things in life with my wife.”

This is the fourth in a four-part series celebrating the 50th anniversary of the UC San Diego School of Medicine. See part 1, part 2 and part 3.

Share This:

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.