By:

- Christina Johnson

Published Date

By:

- Christina Johnson

Share This:

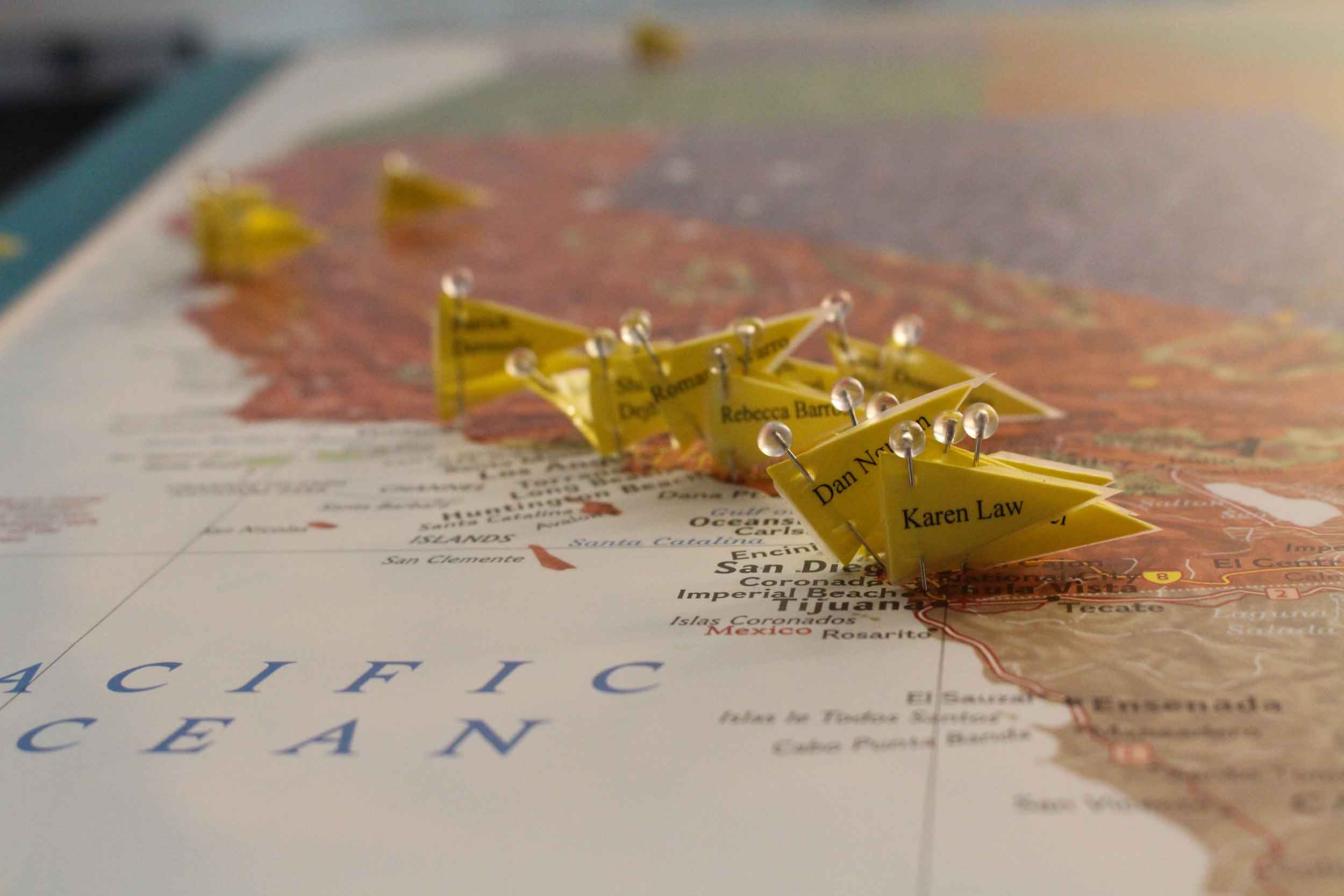

The Envelope Please

Medical students learn residency fate on Match Day

Photos by Erik Jepsen/UC San Diego Publications

Statistics on this year’s graduating class:

- 18% of graduating students are pursuing part or all of their residency training at UC San Diego Medical Center

- 70% percent are pursuing part or all of their residency training in California

- 42% percent are entering primary-care specialties

- 3 students are moving onto military residencies. They were informed of their placement in advance of Match Day.

On March 21, the second day of spring, 116 graduating seniors from the UC San Diego School of Medicine joined thousands of medical students across the nation to simultaneously open “Match” envelopes, revealing where they will spend the next three to seven years as a medical resident.

Dr. Carolyn Kelly, associate dean for Admissions and Student Affairs at the UC San Diego School of Medicine, kicked off the ceremony at the Medical Education & Telemedicine Building with a welcoming speech and hearty congratulations to the class. But the highlight, for most, was the moment when the soon-to-be physicians were invited to approach the table, find their envelope and learn their fate.

The audience of family, spouses, friends and alumni had minutes earlier been coached by Kelly and Dr. Jess Mandel, associate dean for Undergraduate Medical Education at the School of Medicine, on proper Match Day etiquette: A “match” at a hospital in Philadelphia should not elicit an “It’s so cold there. Was that your first choice?” but rather a smile and “Congratulations.”

Neither students nor the residency programs they apply to decide where they will complete their medical residencies. It’s a ranking game that from the outside feels like something between an NBA draft and an arranged marriage, with a computer thrown in and champagne at the end to celebrate.

Students rank their top choices; residency programs do the same, and the heaps of wish lists are submitted to a central computer in Washington, D.C. for a gargantuan numbers crunch the National Resident Matching Program calls “the algorithm of happiness.” There is no appeals process.

Yes, the computer could electronically deliver the “matches” in encrypted files, but that would drain the drama from a day most physicians vividly recall and some describe as the biggest day of their lives.

“We are all nervous about Match Day,” said Inga Wilder, a senior at UC San Diego School of Medicine. “It’s the uncertainty. You can’t plan anything. But I am graduating. I am going to be a doctor in a couple months. I can’t complain.”

Wilder, 30, has reason to be proud. She grew up in Compton, and she and her brother, who joined her at Match Day, were the first in their family to graduate from college. Wilder, a high school valedictorian, went to UC Berkeley and originally planned to get a Ph.D. in microbiology before experience in a lab convinced her she was “more of a people person.”

Standing beside her brother, she opened her envelope and smiled: “I got my first choice,” she beamed, a residency in full-spectrum family medicine at the Ventura County Medical Center, helping underserved communities.

“I am so excited,” she said. “This is one of the best family medicine programs in the country. I am going to work really hard, but when I leave I will be really well trained. And if I have to work on Christmas or Thanksgiving, I can make it home in time to have dinner with my family.”

At UC San Diego, Wilder was part of the University of California’s PRIME-Health Equity program, a dual master’s degree-M.D. program designed to train physicians to serve at-risk populations. Her master’s project with urban youth in East Los Angeles solidified her interest in helping those most likely to fall through the cracks of the health care system.

“In high school, I noticed things were different in my community,” Wilder, a former National Institutes of Health Academy Fellow, said. “There were long waits and the doctors didn’t look like me. I wanted to change that. Family medicine is a perfect fit. If I had wanted to become a surgeon, it would have been harder to get back to my roots.”

The algorithm of happiness was also kind to Heyman Oo, a 28-year-old senior who took a year off from medical school to pursue a master’s degree in Public Health at Harvard. Like Wilder, Oo wants to help those in need, in her case children.

An immigrant from Burma whose family moved to the Bay Area when she was 4 years old, Oa was accepted into the Pediatrics Leadership for the Underserved (PLUS) Program at UC San Francisco, designed to train and inspire future leaders in pediatrics, in research, policy and advocacy for underserved children.

“We will be trained in public speaking, and learn how to write op-ed pieces, in preparation for leadership roles,” Oo explained. Her ultimate goal is to be “at the table” for high-level discussions on health care policy and reform. She is especially interested in addressing the “social determinants of health that don’t get sufficiently addressed in medical school but are really important to wellbeing.”

Photo by Christina Johnson/Health Sciences Communications

“For a long time growing up, I didn’t want to become a doctor because my parents were,” said Oo, who worked extensively with immigrant communities in San Diego while in medical school. “It wasn’t until I went to Thailand and worked at a border clinic for Burmese migrants and refugees that I met all of these international doctors and I saw how many options there are.”

Alfred Kaye’s situation going into Match Day was a bit different than most, as he and his wife have 8-month-old twins and his wife is also pursuing a career in academia, in art history.

Fortunately for the family, Kaye, 31, was matched in a psychiatry residency program at Yale, where his wife has been offered a postdoctoral position at the Yale University Art Gallery.

Kaye, part of the university’s M.D.-Ph.D. program, will be studying post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and how a single traumatic event might permanently alter the way the brain processes information, in addition to receiving clinical training in psychiatry. His dream is to become a professor and run a laboratory that studies the biological basis of mental disorders.

“I’ve seen a lot of patients with PTSD at the VA Hospital,” said Kaye, who was born and raised in Los Angeles. “I’ve seen how debilitating it is and how vast the cost is to their lives.”

“It may be that people never get over their fear, but we may be able to strengthen the inhibitory connections that dampen and control the fear response,” he said. “The time is ripe for this type of approach.”

Share This:

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.