San Diego’s New Graduation Policy on Course to Score Big Wins and Losses

Published Date

By:

- Inga Kiderra

Share This:

Article Content

SDUSD grads. Photo courtesy SDUSD

A rigorous new “college prep” graduation requirement in the San Diego Unified School District looks likely to produce more college-eligible students but even more who will fail to graduate entirely, according to a report by the San Diego Education Research Alliance (SanDERA) at UC San Diego.

In the class of 2016, the first class subject to the new requirement, about 10 percent more students may become eligible to apply to the California State University and University of California systems, but as many as 16 percent more students may not graduate at all. That translates roughly to 650 more students ready for higher education and 1,000 more who will find themselves in June without a high school diploma.

Students from historically underserved populations are the most negatively affected.

The report – “College Prep for All: Will San Diego Students Meet Challenging New Graduation Requirements?” – is co-authored by Julian Betts, executive director of SanDERA and professor of economics at UC San Diego, with Sam Young, a doctoral candidate in economics at UC San Diego, Andrew Zau, senior statistician for SanDERA, and SanDERA Director Karen Bachofer.

“The district has taken several steps to help students at risk of not graduating, but should consider introducing supports for at-risk students as early as middle school,” said Betts. “At the same time, SDUSD should consider alternative routes to a high school diploma.”

Many major urban school districts, including those in Los Angeles, San Diego, San Francisco and Oakland, have recently adopted a bold reform that seeks to equalize access to college. These districts have changed their high school graduation requirements, making college preparatory coursework mandatory – specifically in what is called the “a-g” course sequence, or 30 semester-long courses in assigned subjects required for admission to UC and CSU. While the university systems require grades of C or higher for admission, San Diego Unified is requiring grades of D or higher for a high school diploma.

The SanDERA report is a detailed study of the impact of the reform in San Diego. Using data through August 2015 (as students entered their final year in high school), the analysis suggests the new graduation requirement is having both positive and negative consequences.

Students in the class of 2016 and later are taking, and passing, significantly more a-g courses than did earlier cohorts. It is likely that the percentage of students in the class of 2016 who will graduate with grades of C or higher and therefore be eligible to attend the UC and CSU could rise by as much as 10 percentage points.

Several negative side-effects of the reform that were feared and predicted now appear to be unfounded. “We tested whether, for the classes affected by the new policy, grades fell, absences rose, or more students left district-managed schools to escape the graduation requirement. We found little evidence of any of these possible side effects,” said report co-author Young.

The bad news is that, unless students greatly accelerate their course-taking in their senior year, the graduation rate in 2016 could be as low as 72 percent. This compares to a graduation rate in June 2014 of 87.5 percent.

Students at risk of not graduating on time could still meet the requirement, the co-authors note. The district has implemented online credit recovery courses that satisfy the a-g requirements and, if students take them and pass, the graduation rate may be higher. However, as of August 2015, about 12 percent of students in the class of 2016 had more than a year of coursework to complete in a single subject area. More worrying, Betts said, almost 15 percent of students had more than a full year of coursework to complete in not just one but two or more subject areas during 2015-16.

The subject areas causing the greatest barriers are English, mathematics and world languages.

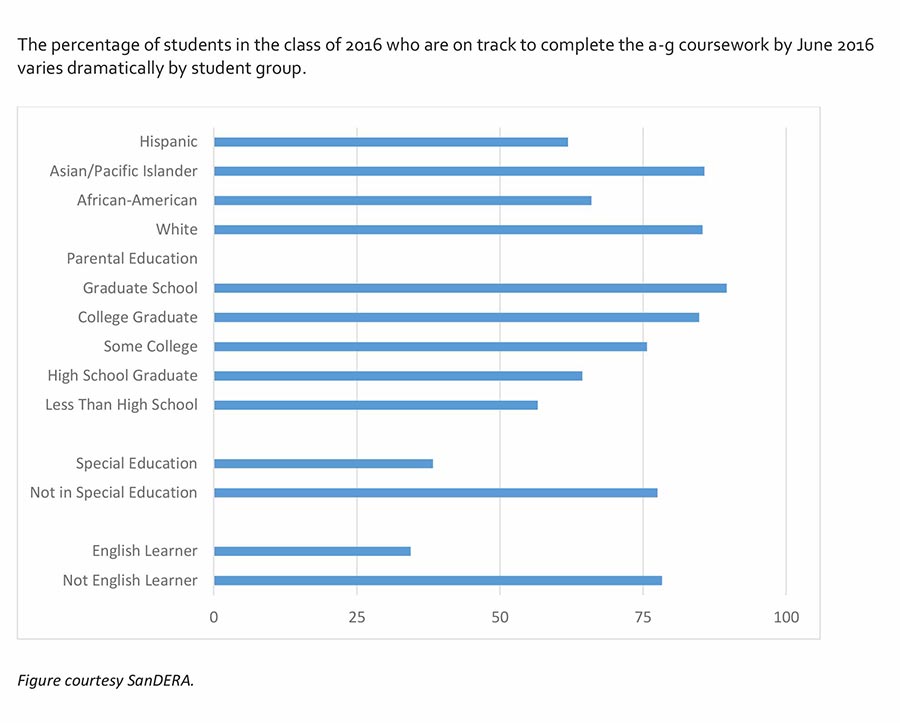

The projected graduation rates vary markedly across student groups. Fewer than half of students in the class of 2016 who were English Learners or who received special education services in ninth grade are projected to complete the required a-g coursework. Fewer than two-thirds of students in the following groups are projected to complete the coursework by June 2016: students whose parents’ highest degree is a high school diploma or less, Hispanic students, and African-American students.

“A policy issue that emerges from the analysis is how SDUSD can best support its students,” said Betts. “Actions taken to date include remedial measures such as expanding summer school and introducing online credit recovery courses. But in addition to remedial measures the district may wish to consider more preventive measures – like its recent move to widen accessibility to world language courses in middle schools.”

Student performance in grade six, the researchers found, can predict a-g completion well, suggesting that students at risk of not graduating under the new requirement can be identified and supported, especially in the problematic areas of English and mathematics, well before they reach high school.

Betts and his colleagues are also urging the district to fully articulate how it will satisfy stipulations in the California Education Code mandating alternative routes to a high school diploma, including a Career and Technical Education route.

The study was supported by funding from the Yankelovich Center for Social Science Research at UC San Diego.

A final version of the report will be published by the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) in late April 2016.

Share This:

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.