By:

- Cynthia Dillon

Published Date

By:

- Cynthia Dillon

Share This:

From Prison to Physics: ‘Oh, the Places You’ll Go!’

It took a punch and a trigger to land Sean Bearden in prison in 2005. It took a mentor named Ms. Rose, armed with a Dr. Seuss book, to set him on his journey to where he’s at in 2020—a scholar of physics who was just awarded a 2020-21 President’s Dissertation Year Fellowship at the University of California San Diego.

UC San Diego Ph.D. Candidate in Physics Sean Bearden. Photo courtesy of Sean Bearden

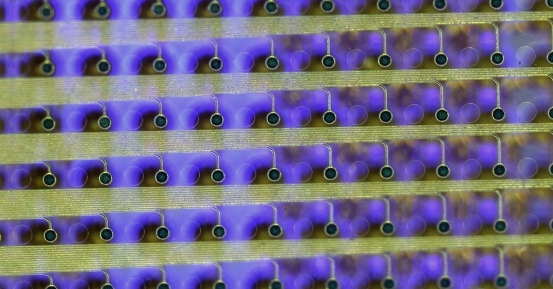

Mentorship is nothing new for Bearden, who now works with Department of Physics Professor Massimiliano Di Ventra researching the application and development of memcomputing systems—a novel computing paradigm considered by some as an alternative to quantum computing.

“Sean is an extremely careful researcher and a deep thinker. He is also one of the most determined and resourceful students I ever had: he does not get easily discouraged by the unavoidable setbacks we encounter in research,” said Di Ventra. “This trait is one of the best indicators for future success.”

But for inmate Bearden, future success was a question, and mentorship a novelty—until he met Ms. Rose, whom he refers to as an anomaly. In addition to being his prison job supervisor, she was also a “history nerd” who enjoyed trivia. So one day, she randomly asked him, “Hey, do you know that guy Nikola Tesla? Did you know he fell in love with a pigeon?”

Bearden explained that he didn’t know that (much less that he would be mastering knowledge in the same field as Tesla, a physicist who invented the first alternating current motor). He admits that he was more concerned at the time with getting to a class for inmates convicted of violent crimes.

The consequences of choice

“I got struck by an individual, and I chose to shoot him with a pistol,” said Bearden. It was a choice that led to his six-and-a-half-year incarceration in New York State Correctional Facilities. The state required Aggression Replacement Training, which led him to a prison facilitator job in transitional services for inmates, where he worked with Ms. Rose.

“There were some perks in it for me,” said Bearden. “I was going to make 25 cents an hour versus the 15 cents an hour I was making before—that’s a lot of money in prison.” He added that the job also would result in a Department of Labor certification, meeting a vocational training requirement for a skill needed upon release. “And, then, I also got to work with Ms. Rose. It was fun, and she made me laugh, which broke up the monotony of prison.”

Bearden explained that he took the job of class facilitator, after completing the course himself, not because he felt like he mastered his aggression to the point of needing to “spread the word on how to do prison,” but rather as an acceptance of the situation he had gotten himself into.

“It’s hard to help people who don’t want to be helped, so I would remind them that I was an inmate too; I didn’t care if they learned how to replace their aggression, I just wanted to see them go home at that parole board, and I didn’t want to be the reason that that didn’t happen,” he said.

Bearden said that he also reminded fellow inmates that he was doing his job as part of the vocational training requirement, which put them all in the same kind of situation—doing what they had to do to get out of prison.

He noted that even though they were trying to help each other, it was a forced situation, so he started to learn from Ms. Rose just how to deal with it—how to get through to people.

“Ms. Rose treated us like people. When she was talking to you, you felt like a person. And that’s rare in prison; counselors don’t really do that,” explained Bearden. “Ms. Rose was different, she was an anomaly, and we all knew it. Everybody in the prison knew about her. Even before I met her, I knew her reputation in the prison. I really didn’t know why she was so invested, but her reputation was that if she could do the right thing, she would. But she wasn’t an inmate—she was an outsider.”

A rosier future

Bearden explained that as inmates, it’s great to have an ally, but inmates don’t really trust anybody who’s not one of them. So, Ms. Rose had to break through to them in different ways. According to Bearden she was caring but sarcastic. She offered doses of reality when they were needed, so inmates could learn to make the choices to go to the next step—whatever that was.

Ms. Rose. Photo courtesy of Sean Bearden

“We all have a next step if we have a common goal. She didn’t want to hold us back,” said Bearden. “I remember this one time—there was a class of inmates who had just finished a few weeks of this training, and Ms. Rose walks in the last day with a Dr. Seuss book in her arm. And the book was ‘Oh, the Places You’ll Go.’ And everybody looked at me as if I’m supposed to explain what’s about to happen.”

He noted that the book, unfamiliar to many inmates, is commonly given to graduates of high school and college in celebration of their achievement.

“I dropped out of high school. I had a GED. They look at me, and I am just as confused as they are,” recalled Bearden. “I didn’t know what was about to happen, but she sat there and read the Dr. Seuss book, and we were just like why is this lady doing this—reading children’s books. But that’s what she was trying to do—just show us that there is a future, you have to better yourself; you have to prepare for this.”

The road to education

According to Bearden, Ms. Rose’s love of learning started to rub off on him, and he started to appreciate education. He began taking college courses through Ohio University’s Independent and Distance Learning program. The years of his prison term passed, during which he earned an associates’ degree. In 2011, he was granted his freedom.

“You can imagine the euphoria when you leave prison—amazing feeling—but it wore off quickly because the reality sets in that you have to prove yourself—to parole, to your family, to society. So, my focus was to continue with education," said Bearden.

In 2012, he enrolled at the University of Buffalo to earn a bachelor’s degree in physics, with a focus on proving he belonged as the outsider. At age 26, Bearden felt out of place among students who were 21 years old or younger.

“They looked at me like I’m the old man. They didn’t want to hang out with me,” he said, adding that instead he focused on building his curriculum vitae (CV)—gaining accomplishments—because then he’d have a piece of paper to show that he’d changed.

Finding community

“That first semester, trying to come up with things to achieve in isolation, I couldn’t come up with anything—no one was inviting me to things to do—volunteering or anything,” said Bearden. “So I drew on Ms. Rose being the outsider, and thought maybe others would accept my help if I’m willing to help them.”

So, he went to the combined Martial Arts clubs and volunteered. Then he was invited to become a college ambassador for the physics and mathematics departments at the University of Buffalo, and, eventually, he revived a Society of Physics Students chapter on campus—getting students involved to create more activities and events for participation because they were all building their CVs.

“I started to realize we can accomplish more together, and it really doesn’t matter if you have the same exact thing that I have on my resume,” he said. “I just really started opening up to the idea that I need to be part of a community, and I need to stop isolating myself by thinking I’m so different.”

Bearden said that when he started the journey, it was a lonely one, and he had no idea where it was going and where it was going to end up.

“And that day when Ms. Rose came in and read to the class, ‘Oh, the Places You’ll Go,’ I don’t think she or I knew that I would end up in a graduate program at UC San Diego—which happens to be the home of the Dr. Seuss Collection.”

Share This:

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.