By:

- Robert Monroe

Published Date

By:

- Robert Monroe

Share This:

Hunting Atmospheric Rivers

UC San Diego scientists preparing to capture data from critical source of California’s water supply

An Air Force C-130 “Hurricane Hunter” aircraft at San Diego’s Brown Field. Photos by Erik Jepsen/UC San Diego Publications

As the traditional peak of a new water year approaches, researchers at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego are poised for more chances to understand the phenomenon that can make or break California’s annual water supply.

Atmospheric rivers are bands of moisture in the sky that can carry more water in them than any terrestrial river in the world. These bands—some that originate in Hawaii are known as “Pineapple Express” storms—can deliver as much as half of California’s water supply in a handful of precipitation events every year. In 2016-17, they brought enough rain and snow to end a crippling drought.

U.S. Air Force Maj. Ashley Lundry joined Scripps Oceanography scientists Nov. 29 to plan atmospheric river reconnaissance missions beginning in late January

Scientists at Scripps’ Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes (CW3E) are leading a field effort with the National Weather Service to utilize two Air Force C-130 “Hurricane Hunter” aircraft for a month starting Jan. 25. They hope that during that time period, atmospheric rivers will set up over the Pacific Ocean at least a few times. The planes will be stationed in Hawaii and either Washington state or California, and if the conditions are right, fly through atmospheric rivers, dropping instrument-laden, parachute-tethered dropsondes across the width of the storms and to collect data.

“We could be dropping anywhere from 25 to 50 dropsondes per mission into an atmospheric river, and all of that data will be sent to the National Hurricane Center and then out to the public and ingested into forecast models. This same data also would be made available to Scripps researchers,” said U.S. Air Force Maj. Ashley Lundry, 53rd WRS aerial reconnaissance weather officer and chief scientific officer.

The ultimate goal, said CW3E Director F. Martin Ralph and project lead, is to provide “research and information to the National Weather Service to help better inform Western decision-makers regarding storm impacts, water management, and flood mitigation.”

The airborne data gathered this year feeds directly into the nation’s leading weather forecast model run by the National Weather Service, as well as into other weather models run globally and into an experimental model at CW3E (run at UC San Diego’s San Diego Supercomputer Center).

F. Martin Ralph, a leading atmospheric river researcher, said data collected on flights through storms will be fed into weather forecast models produced by the National Weather Service

“We are developing new scientific understanding of how atmospheric rivers work, as well as advanced tools for monitoring, and predicting atmospheric rivers. Data from these flights are key to achieving our goals,” said Ralph while touring the cargo hold of a C-130 offered for tours at Brown Field last week.

The project supports the Forecast-Informed Reservoir Operations (FIRO) program with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Sonoma County Water Agency, as well as California’s Department of Water Resources (DWR). FIRO administrators are exploring the potential for reservoir operators to consider forecasts of precipitation more often in their decision-making, and forecasts of atmospheric rivers are particularly important for this, said Ralph.

Ralph with Air Force crew members who plan to fly through atmospheric rivers and deploy data-gathering instruments from Hurricane Hunter aircraft

CW3E is also a partner in a major project, funded by DWR and led by NOAA’s Physical Sciences Division, in the San Francisco Bay area to enhance zero- to 12-hour forecasts of heavy precipitation from atmospheric rivers using state-of-the-art scanning radars installed in the region. The Atmospheric River Reconnaissance aircraft data will reach far offshore, enhancing the lead time for storms that generally move from west to east.

For the past two decades, researchers at Scripps, NOAA, U.S. Geological Survey, NASA, the Department of Energy, and other universities have identified and characterized atmospheric rivers and come to understand how critical they are to California, the U.S. West Coast and other locations globally, where a few rainy days can make the difference between a severely dry year or an above-average precipitation year.

Scientists, however, have yet to fully understand what physical processes modulate their position and strength at landfall, and how much of their precipitation will fall as rain and snow over California, or how much will keep on flowing to points east without producing a drop. Development of these capabilities in particular could help mitigate the risk of near-disasters like last year’s Oroville Dam spillway incident, which was triggered partly by an unusually strong, warm and long-lasting atmospheric river.

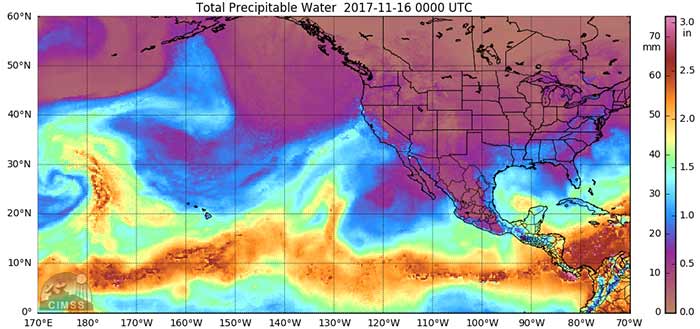

Visualization of a mid-November atmospheric river showing a band of moisture reaching California. Image: University of Wisconsin

Researchers at Scripps have found evidence, though, that in an era of rapid climate change, atmospheric rivers can be expected to become less frequent but more intense. They might actually bring more water to California in coming decades, but the delivery could be so intense that it challenges the state’s ability to store water through times of drought and prevent floods in times of excess. Ralph said researchers hope that the new methods under development could be useful in future reservoir operations so as to mitigate these risks.

CW3E works directly with water managers in the West to develop science and tools they could use to better prepare for those fluctuations. This includes being able to capture precipitation when it occurs to offset periods of drought, or to better anticipate flood risk.

— U.S. Air Force Tech. Sgt. Ryan Labadens, 403rd Wing Public Affairs contributed to this report

Share This:

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.