By:

- Corey Levitan

Published Date

By:

- Corey Levitan

Share This:

(Clockwise from top left): Steve Boyer, Chris Pizzo, Brownie Schoene, Frank Sarnquist, Rick Peters, Chris Kopczynski, Peter Hackett, John West, Dave Graber and Karl Maret reunite 40 years after their Mount Everest expedition.

Summit of Science

First scientific expedition up Mount Everest reunites 40 years later

The tools of a scientist often feature items like microscopes and petri dishes. For an elite group of physiologists and biologists 40 years ago, they also included ice axes and belays.

In the fall of 1981, 14 scientists and six climbers embarked on the first scientific expedition to the Mount Everest summit. The American Medical Research Expedition to Everest (AMREE) was an ambitious but dangerous three-month mission to investigate exactly what happens to human lungs, hearts and blood at extreme altitudes, with and without supplemental oxygen.

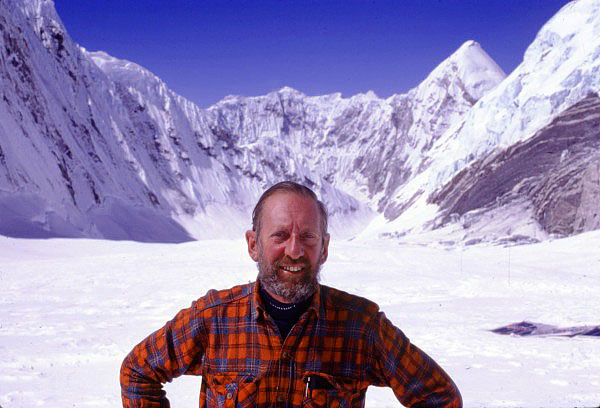

John West, leader of the first scientific expedition to summit Mount Everest poses at a base camp, altitude 20,700 feet, before the final ascent.

In early November, 12 of the 16 surviving members reunited to mark the anniversary at the home of expedition leader John B. West, M.D., Ph.D., Distinguished Professor of Medicine and Physiology at UC San Diego School of Medicine, and his wife, Penelope.

“Before AMREE, no one had ever made measurements of human physiology on the summit of Mount Everest—and no one has since, either,” West, 92, told his former climbing partners, nine of whom gathered on the backyard patio and two of whom joined via Zoom.

Chris Kopczynski, Chris Pizzo and Peter Hackett, all of whom attended in person, were the only AMREE members able to make the summit from the expedition’s highest base camp. In fact, they became the ninth, tenth and eleventh Americans to summit Everest. But for a while, it looked like none of the expedition’s members would.

“It was constant 50- to 100-miles per hour winds,” recalled Pizzo, 72, noting that the jet stream had dipped to 8,000 meters. “It was impossible to climb in those conditions. We were running out of food and fuel and everybody was physically shot. I had very little hope that the conditions would suddenly improve and we would get a window to make a summit shot.”

But then the jet stream lifted.

Pizzo used supplemental oxygen on his way up, like the two other summiteers after him, but he removed it to measure ventilation during maximal steady-state exercise. Then, at the summit, he removed it again for several minutes.

“Sitting there, off oxygen, you feel fine,” he said. “But I needed something out of my backpack, and just the motion of getting up and turning around—that minimum of activity—had me in a state of such extreme hyperventilation that any other exertion was impossible for over a minute until I had restored a more functional PO2 (partial pressure of oxygen).”

Chris Pizzo takes samples of his alveolar gas at the summit of Mount Everest on Oct. 24, 1981.

What Pizzo retrieved from his backpack was an alveolar gas sampler specially designed by another expedition member, Karl Maret. After catching his breath, Pizzo puffed into it and became the only member able to fulfill the expedition’s main mission of capturing breath samples at the summit.

West brought the samples back to his UC San Diego lab, where he analyzed them on a mass spectrometer. What he discovered were specific physiologic changes that occur in the lungs and allow humans to breathe at the top of the world. The findings became fodder for 35 published scientific papers.

The partial pressures of alveolar and arterial oxygen, and the partial pressure of carbon dioxide, all fell with altitude, as was previously known. However, at approximately 29,000 feet, a minimal partial pressure of oxygen sufficient to allow physical activity is defended by what West called “an enormous amount” of hyperventilation.

“Chris Pizzo was breathing at five times the normal rate, but very little carbon dioxide was being exhaled,” West said, adding, after a long pause: “You could argue that it’s a very strange coincidence, but the very highest point in the world is right at the limit of human tolerance to lack of oxygen.”

AMREE wasn’t West’s first scientific mountain-climbing expedition. In 1960, he attempted to climb the world’s fifth-highest mountain, Makalu, to study the effect of low oxygen, tagging along with Sir Edmund Hillary and a small group of other physiologists. Makalu (27,766 feet) sits on the Nepalese-Tibetan border and is just 12 miles from Mount Everest.

John West tests his lung capacity at Camp 2.

West was asked to join that expedition with no experience in either high-altitude physiology or mountaineering. While attending a conference more than 60 years ago, West recalled a stranger seated next to him asking: "Do you know that there’s an expedition going to Mount. Everest—I didn’t—and would you be interested in going as a physiologist? I was.”

The so-called Silver Hut Expedition was intended to show humans could summit Mount Everest without supplemental oxygen by first acclimatizing to high altitudes. The plan was to climb to 20,000 feet on Makalu and spend several months there, then attempt the summit without oxygen. Unfortunately, the climbing team fell ill before reaching the summit, but West was still able to take some measurements at 24,400 feet.

“About that time, I wondered whether it would be possible to get measurements on the highest point of the world,” said West, who went on to author 427 articles and 21 books about respiration, including the still-used “Respiratory Physiology: the Essentials.”

In January 1978, West, expedition climbing leader John Evans and biology professor F. Duane Blume applied to Nepal for AMREE’s climbing permit. While they waited for approval, the first summiting of Mount Everest without supplementary oxygen was accomplished by European mountaineers Rheinhold Messner and Peter Habeler.

This proved the feat possible, West said, “but I wanted to know how it was possible since all the oxygen available at that altitude is already required for the body to function at rest.”

Back at the reunion, Kopczynski raised a glass of Champagne and crystalized the group’s sentiments during one of many toasts: “Here’s to you, John West, for pioneering your science for the world to reap the benefits for a long, long time.”

Most reminiscences were similarly pleasant, but one reminded the group of how close the expedition came to making history for the wrong reasons.

Hackett, a relatively inexperienced climber, became the third and final expedition member to summit and, unbeknownst to the group, the first person known to have climbed from Everest’s south summit to its true summit by himself and return. (The last climber to try for the highest part of the summit, Mick Burke, is believed to have fallen to his death in 1975. His body was never recovered.)

Pizzo called Hackett’s unaccompanied journey “probably one of the worst decisions in mountaineering history.” Hackett explained to the reunited group that what motivated him was a question posed by Pizzo: “When are you going to be this close to the summit of Everest again, Peter?” But he also admitted that “hypoxia (oxygen deprivation) may have played into it.”

Not long into his summit, Hackett told the group, the realization hit that he wouldn’t be able to take any scientific measurements because his quest had become merely one of surviving “a desperate attempt to try and get up and get back down before it got dark.”

Not only did the sun set on Hackett, but on the way down Mount Everest, he found himself hanging upside-down by his left boot on the Hillary Step, a nearly vertical, 40-foot rock face. As he recounted the story to the reunion group, he turned to Pizzo and said, “Thank God you were waiting there for me.”

Pizzo replied: “Thank God you had a head lamp or we never would have found our way back.”

The AMREE members reunited in 2006 for the expedition’s 25th anniversary, but West said this time was extra-special:

“It’s very remarkable that so many people are alive 40 years later, so I wanted to mark this historic occasion one last time because it’s quite obvious that we’re not going to get to do this again.”

Share This:

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.