By:

- Erika Johnson

Published Date

By:

- Erika Johnson

Share This:

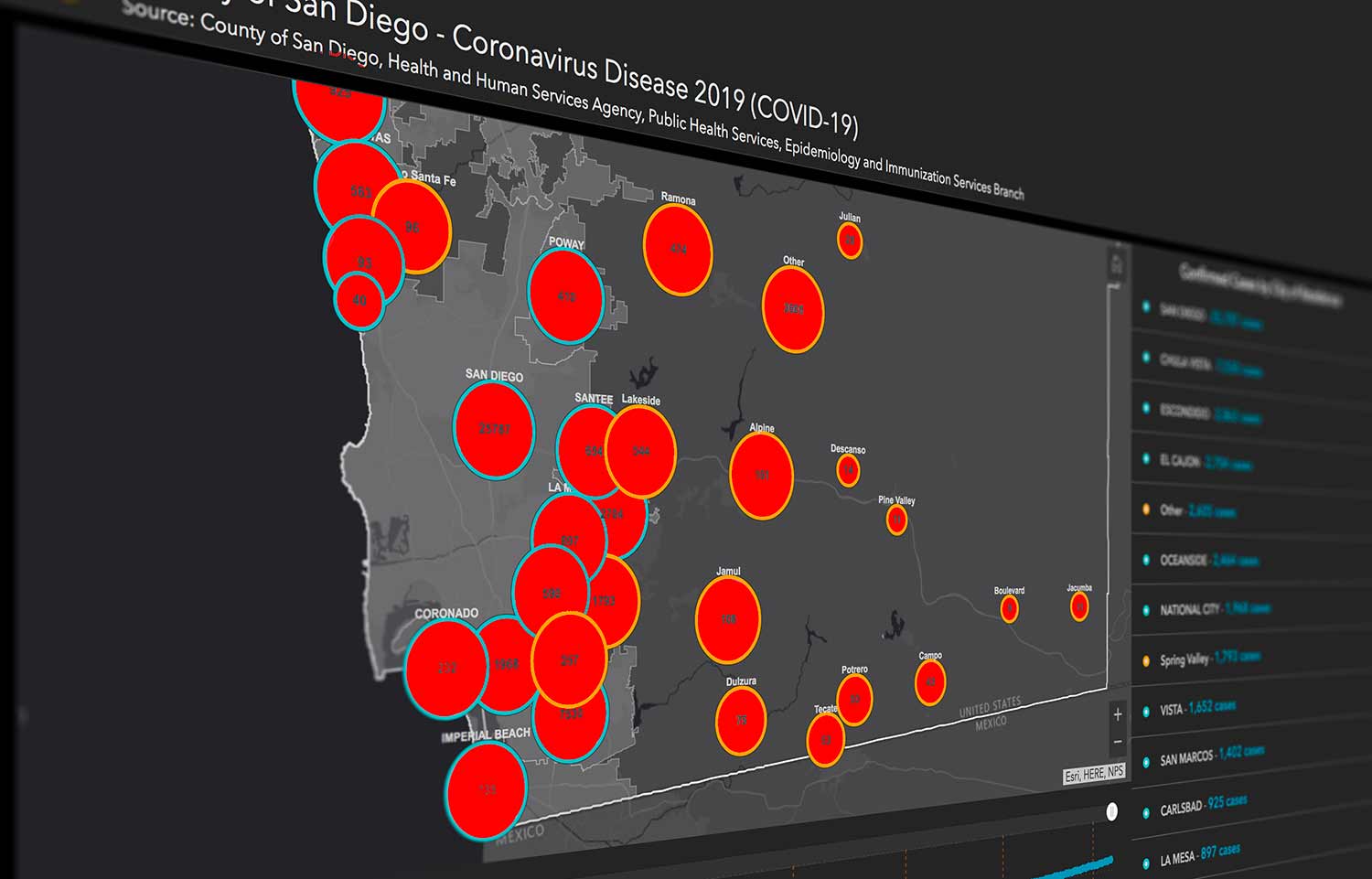

The Unequal Spread of COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic has flooded communities that are already at a disadvantage, disproportionately affecting underserved populations. In local neighborhoods such as Chula Vista, Southeast San Diego and El Centro—where some of the highest local infection rates have been reported—there are crowded residential complexes where physical distancing becomes challenging. There is also a lack of access to hospitals, which can mean traveling across the county to receive care, sometimes via public transportation. Many of these locations are also food deserts with limited access to affordable and nutritious food, affecting the health of residents.

Maria Rosario (Happy) Araneta, professor of family medicine and public health at UC San Diego School of Medicine.

“Your zip code is often a more important determinant of your health than your genetic code,” explained Maria Rosario (Happy) Araneta, professor of family medicine and public health at UC San Diego School of Medicine. “Achieving health equity requires access to care, decent housing, running water, healthy food, green outdoor spaces and economic and educational equality.”

Research and service conducted by UC San Diego faculty, students and staff are pinpointing where these inequities are most prevalent in San Diego. Interventions have been developed such as increased testing sites, new curricula focused on culturally inclusive health care and delivery of resources to vulnerable patients with chronic ailments.

A disproportionate rate of infection

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there is a higher prevalence of COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations and deaths among American Indian, Asian, Black and Hispanic populations. These high rates are often tied to structural determinants of health. For instance, the Navajo Nation surpassed New York State with the highest infection rate earlier this year. An important factor that contributed was the lack of running water in nearly 40% of Navajo households, preventing people from following the first intervention recommended—washing your hands. In addition, nearly one out of every five nurses in California are Filipino. Working directly with sick patients, they comprise nearly 70% of all nurse deaths in the state.

What can be done? Araneta explained that it is critical to collect more data about local populations to better overcome barriers to testing and treatments. “When infections among the ‘Asian’ population is reported, we don’t know if they are Chinese, Vietnamese or Korean,” said Araneta. “And we don’t know what languages contact tracers need to speak. A contact tracer who is familiar with the practices of the community will be able to elicit honest responses and opportunities for prevention.”

In addition, some communities may avoid testing for a variety of reasons. Among communities with a large number of undocumented individuals, there is a reluctance to be tested for COVID-19 for fear that a positive result will be reported to a government agency. Other individuals worry that a positive result may cause them to lose their job. In some cultures, including Muslim families, it may be considered inappropriate for a woman to quarantine in a hotel by herself.

Bringing care directly to communities that need it most

To improve access to care, UC San Diego is partnering with local organizations to expand testing sites into local communities most impacted by COVID-19. A recent $5 million grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has launched a testing program in San Ysidro focused on pregnant women and children. Testing efforts will employ an automated system capable of processing up to 6,000 tests per day at one-third the cost of current clinical COVID-19 tests. The project also will involve finding new ways to communicate with persons and communities of color who have long suffered from health inequities and lack of resources due to systemic racism.

Dr. Susan Little, professor of medicine at UC San Diego School of Medicine and principal investigator of the UC San Diego Janssen trial.

UC San Diego Health is also part of an international clinical trial to test vaccine candidates for the coronavirus. There is an emphasis on participation in underserved communities, particularly those of color, that have shown higher rates of both hospitalization and death due to COVID-19. To permit easier access to the study in these communities, a testing site has been established in National City—in the parking lot of Toyon Park—which is scheduled to operate through October 2022. In a different vaccine trial, a mobile clinic will be used to bring vaccination testing directly to heavily impacted communities and neighborhoods.

“Many communities of color are experiencing higher rates of hospitalization related to COVID-19 than are observed in white, non-Hispanic people,” said Dr. Susan Little, professor of medicine at UC San Diego School of Medicine and principal investigator of the UC San Diego Janssen trial. “It is important that these communities are represented in COVID-19 vaccine clinical trials so that we understand if the vaccine will work well within these groups.”

In addition, the UC San Diego Student-Run Free Clinic Project received support through the CARES Act that was awarded to the UC San Diego Hispanic Center of Excellence. Through this funding, the clinic was able to provide phones to enable patients to connect with physicians via televisits and Zoom calls. More than 140 medical students volunteered to deliver medicine and food to patients. Ninety two percent of the clinic’s patients are severely food insecure, and in partnership with Feeding San Diego, they are able to provide a “food prescription” with healthy fresh fruits and vegetables, as well as nonperishable items such as beans, rice and oatmeal.

The clinic’s regular support group also went virtual. “More people are participating now as they struggle with isolation,” said Dr. Natalie Rodriguez, associate clinical professor in family medicine and public health. “The open group is a way for patients to share their struggles and how they are coping—many have chronic issues such as diabetes, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, depression and anxiety, chronic pain or asthma.”

Educating a new generation of equity-minded physicians

This fall, a new Health Equity Thread was launched as part of the curriculum at the UC San Diego School of Medicine under the direction of Dr. Weena Joshi. As part of the program, students are encouraged to launch their own elective classes, and they are already making an impact. As an example, medical student Manny Keiler, together with classmates Kevin Gilbert and Edgar Vega, started a blood pressure monitoring mini-clinic in local barber shops that cater to Black customers. They set up a table with their stethoscopes, blood pressure cuffs and health education pamphlets to serve customers, establish trust and empower barbers to become lay hypertension educators. In addition, Alec Calac, an M.D./Ph.D. student, initiated the Tribal Ambulatory Healthcare Experience, an elective in which medical students shadow physicians at the Indian Health Council, a tribally operated Indian Health Service facility in North County, San Diego.

Dr. Natalie Rodriguez, associate clinical professor in family medicine and public health.

Public health continues to advance at UC San Diego with the establishment of the Herbert Wertheim School of Public Health and Human Longevity Science. The school was established in 2019 with a $25 million lead gift from the Dr. Herbert and Nicole Wertheim Family Foundation, with an emphasis on research and education designed to prevent disease, prolong life and promote health through organized community efforts. The new school curriculum is focused on prevention of disease and injury and promotion of health and well-being.

“In global emergencies like the COVID-19 pandemic, the importance and relevance of public health are most apparent and can most dramatically and effectively improve and save lives,” said Dr. Cheryl Anderson, professor and founding dean.

Share This:

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.