By:

- Anthony King

Published Date

By:

- Anthony King

Share This:

Uncovering ‘Icons of Dissent’

From Bob Marley and Tupac to Che Guevara and Osama bin Laden, history professor Jeremy Prestholdt explains the importance—and changing faces—of global figures

Bob Marley flag, Lamu, Kenya, 2008. Photos by Jeremy Prestholdt

In the 1960s, Ernesto “Che” Guevara became an international symbol of radicalism, solidarity and revolution. In the ’90s, his image was revived as both a rebellious role model and a nostalgic fashion symbol. Significant changes also occurred in society’s memory of musicians Bob Marley and Tupac Shakur. In some circles, even Osama bin Laden became a popular anti-establishment symbol—and T-shirt design.

At UC San Diego, Prestholdt specializes in African, Indian Ocean and global history with an emphasis on consumer culture and politics.

But why did people around the world come to see these figures as so important? And how have their meanings changed? These questions lie at the heart of the new book “Icons of Dissent: The Global Resonance of Che, Marley, Tupac, and Bin Laden” by UC San Diego Department of History professor Jeremy Prestholdt.

To answer, Prestholdt explores recurring patterns in what he terms the “transnational imagination,” a way of seeing that frames local circumstances in a global and historical trajectory that ultimately affects collective action.

“These are figures that have been able to capture, and to a degree channel, popular desires for social or political change,” Prestholdt said. “While they came from very different social contexts, offered different visions and drew different audiences, they evidence a recurring phenomenon: attraction to shared symbols that challenge the predominant socio-political order.”

In “Icons of Dissent,” Prestholdt explores the appeal of these four figures over five decades, in part revealing two aspects of an increasingly interconnected world that have not been explored in sufficient depth: the tension between shared global symbols and their local interpretations, and the intersection of political vision and consumerism.

By considering the resonance and selective interpretation of these figures in multiple world regions over time, Prestholdt sheds new light on the transnational and historical factors that define icons. He reveals their changing meaning and the commodification of political sentiment in the modern world.

“Icons of dissent reflect popular sentiment, political sensibility and consumer culture. They transcend cultural and economic boundaries, and they are integrated into consumer trends,” he said. “Because people invest such figures with great symbolic power and develop mythologies around them, icons act as mirrors, allowing us to look back at ourselves, and at our collective anxieties or ideals.”

Memories of iconic figures, from political leaders to pop stars, reveal how so many people seek deeper meaning for their personal experiences in global popular culture and shared symbols.

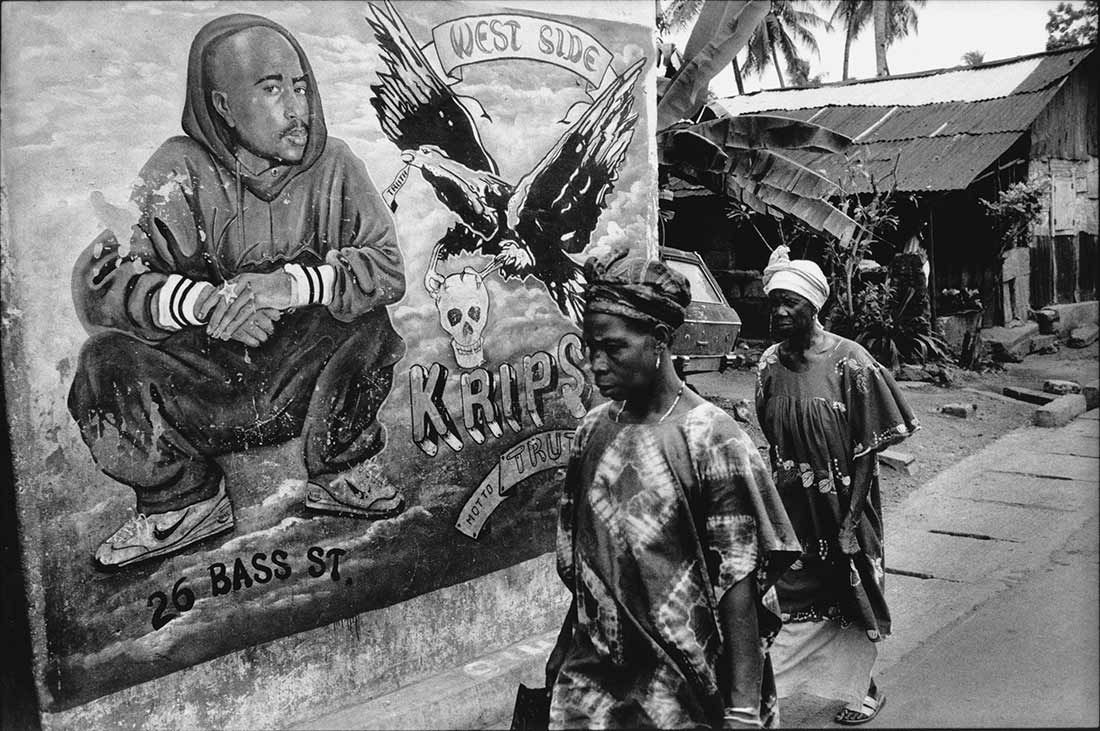

It’s how Tupac’s critiques of social inequalities in the United States transformed him, after his death in 1996, into a generational voice that embodied post-Cold War disillusionment, indignation and rejection of the status quo. As a result, he became a common reference for young people, including insurgents from Guadalcanal to Sierra Leone and Libya—far from Los Angeles, where Tupac lived at the height of his hip-hop career.

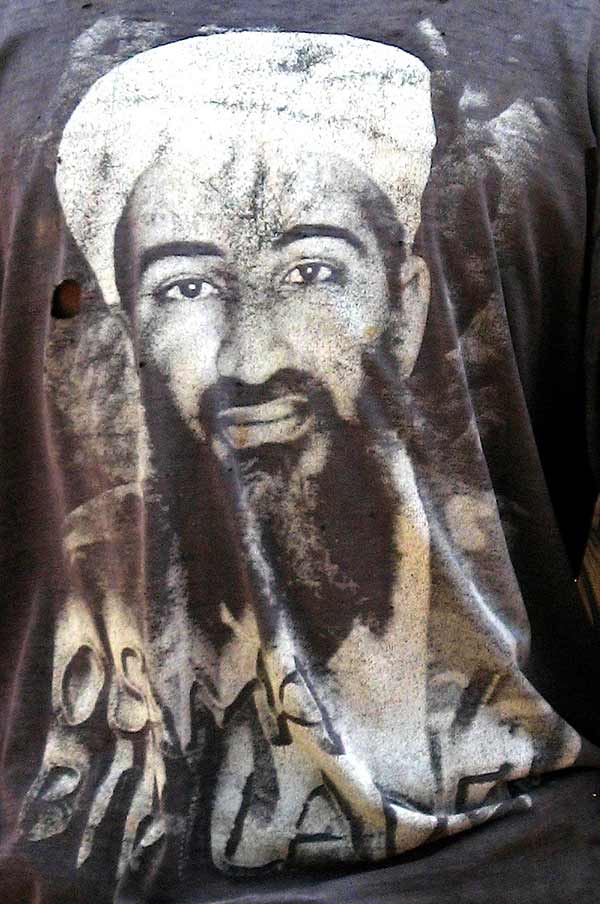

Osama bin Laden T-shirt, Pate Island, Kenya, 2008.

Osama bin Laden, perhaps the most controversial figure in Prestholdt’s research, took on somewhat similar meanings. While most saw him as nothing more than a terrorist and mass murderer, some perceived him to be the embodiment of critiques of political repression and U.S. foreign policy. His image also became broadly commercialized, appearing on everything from T-shirts in South Africa and Venezuela to cologne bottles in Pakistan.

What’s more, icons of this magnitude can take on quasi-religious form, Prestholdt says. Take Marley, for example. A musician from Jamaica, Marley became an international reference for social justice in the 1970s, yet after his death in 1981, greater emphasis on the spiritual elements of his canon eventually transformed him into a “transcendent spiritual figure,” Prestholdt said.

This dramatically increased Marley’s popularity but, similar to the other icons in Prestholdt’s research, it also contributed to an unprecedented commercialization of his image.

Prestholdt says it is society itself that changes the meaning of icons: people collectively alter their narratives about historical figures to serve contemporary needs. While the personal ideologies and actions of these figures help establish them as recognizable individuals, icons often gain far larger audiences as they are “distilled” into an essence of shared ideals or interests, he said.

“For iconic figures to remain relevant, they must be collectively reinterpreted,” Prestholdt said. “The figures that remain in the popular imagination often do so because audiences see them differently in each new historical moment. They ascribe new meanings to them, sustaining them in the collective memory.”

Tupac Shakur mural, Freetown, Sierra Leone, 2000. Photo by Teun Voeten.

At UC San Diego, Prestholdt specializes in African, Indian Ocean, and global history with an emphasis on consumer culture and politics. He is the author of “Domesticating the World: African Consumerism and the Genealogies of Globalization” (2008). He has been awarded fellowships by the National Endowment for the Humanities, Rockefeller Foundation, Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation, Fulbright Foundation, and Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation among others.

Share This:

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.