By:

- Inga Kiderra

Published Date

By:

- Inga Kiderra

Share This:

It Takes a Village or 10: Collective Action Stops Harmful Social Practice

Can people change their ways? Yes. But don’t bother preaching against a culture’s conventions, or outlawing them. Neither will work – or not for long, says Gerry Mackie, associate professor of political science in the UC San Diego Division of Social Sciences. When it comes to stopping a harmful social practice, Mackie says, the people practicing it must band together and abandon it as a group. You must empower a community to change itself.

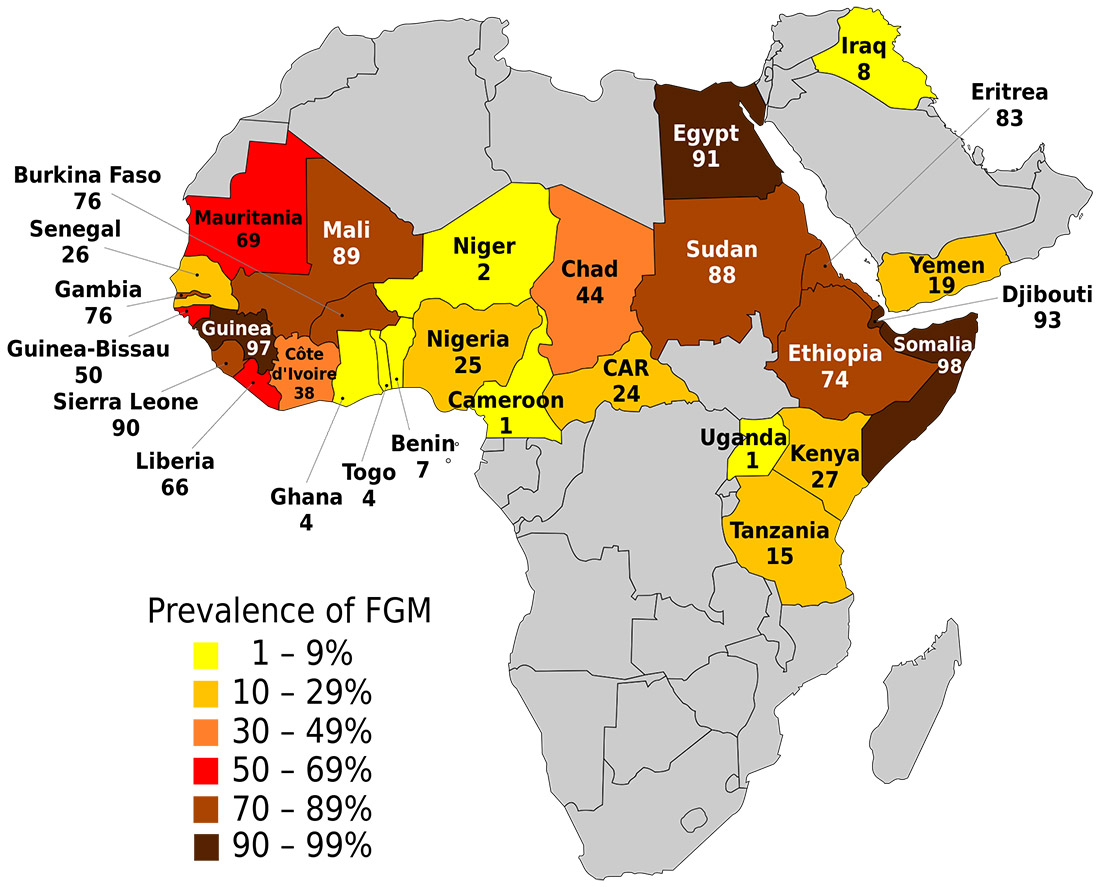

You must also empower a community to change its norms, or its ideas of what is “normal.” Mackie, founding co-director of the Center on Global Justice at UC San Diego, has been studying female genital cutting (FGC) for nearly two decades. Defined by the World Health Organization as “procedures that intentionally alter or cause injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons,” FGC, also known as female genital mutilation or FGM, is concentrated in 29 countries across Africa and the Middle East. It also occurs in parts of Asia, as well as in diaspora communities abroad.

UNICEF estimates that more than 130 million girls and women alive today have undergone FGC and that more than 3 million girls under the age of 15 are at risk every year. Ranging from symbolic pricking to infibulation—or excision of the clitoris and labia and being “sewn shut”—the practices can cause both immediate and long-term trauma. Cutting can lead to hemorrhaging and death and lifelong problems with infections, intercourse and childbirth.

Imam Demba Diawara, Molly Melching, founder of the NGO Tostan, and UC San Diego’s Gerry Mackie are the “improbable collection of characters” who shaped Tostan’s successful methods.

But, Mackie emphasizes, the communities that have been practicing FGC for centuries are not intending harm. Parents who have their daughters cut don't want to see them hurt or disfigured, they want to assure them of being marriageable in their society. And that’s key to understanding how to end FGC.

“They do it because they love their daughters,” Mackie said, “and they will stop because they love them.”

Mackie first began studying FGC as a graduate student. Recently widowed and a single father, Mackie went back to school aged 40. In his first session, he said, he heard about infibulation in Somalia. Infibulation is one of the most severe forms of FGC. It struck him then that the practice was intertwined with marriageability, and he was reminded, he says, of how foot-binding in China – which lasted for a 1,000 years but ended in a single generation – had once been linked to marriageability too.

From there he went on to publish, in 1996, a seminal paper in the journal American Sociological Review arguing that infibulation could end much like foot-binding in China had. The “pivotal innovation,” he maintained, were associations of parents publicly pledging not to bind their daughters’ feet and to not let their sons marry foot-bound women.

He sent the paper to 25 different international agencies, Mackie says. Not one responded. Then in 1998, while proctoring an exam at Oxford, sneak-reading the International Herald Tribune under the table, Mackie came across a story about a nongovernmental organization called Tostan and some villagers in Senegal. They had held a press conference declaring an end to FGC in their intermarrying group. After the exam, Mackie recalls, he went out to the street and did a victory dance under the trees: Here was his theory in practice.

Committing to a new normal in public begins to end a harmful practice.

Mackie packed up his academic paper in a manila envelope once again, addressed it to Tostan’s P.O. Box and sent it off, for the 26th time. A short while later, he got back a 12-page fax from Tostan founder Molly Melching. That began an intense collaboration between Mackie, Melching and local Senegalese imam Demba Diawara. The religious leader observed that it was not enough for one village to give up FGC; for lasting success, many intermarrying villages would have to give it up together. The trio, in the words of a New York Times report, are the “improbable collection of characters [who] shaped Tostan’s methods.”

Since then Tostan – which emphasizes a human-rights based education program and community dialogue, supporting beneficial change in many different areas not just FGC – has helped more villages in Senegal organize collective pledges and mass public declarations abandoning the cutting practice.

The declarations, Mackie explains, are joyous occasions: “The process is positive, celebratory, and forward-looking, not negative, rebuking, or backward-looking.” It is not led by a “few wise outsiders” but involves the efforts of hundreds of local people coming together. And the events themselves can look like parties. People dress in their finest, brandish colorful placards and speak their intentions into mikes for all to hear.

Researchers and activists hope to see FGC abandoned globally within a generation.

Through direct or indirect engagement with the program, Tostan notes on its website, more than 7,000 communities across eight African countries have now publicly declared their abandonment of FGC. Public declaration, however, Mackie cautions, is a high point not the end. More and more abandon the practice over time, he said, as “enough people see that enough people are changing.”

That’s what seems to work best: Encouraging agency in a community and encouraging a new norm to spread. Simply informing people that traditional cutting is unsafe sometimes results in medicalization of the practice, putting doctors and nurses in charge in place of traditional cutters. And criminalizing FGC can drive it underground, making it even less safe and entrenching traditionalists in their positions.

“Change is rarely spontaneous, though – it has to be organized,” said Mackie, who was a labor organizer for a large forestry workers cooperative before his academic career.

Mackie has worked closely with UNICEF on the issue since 2004, helping with a publication on best practices that has been distributed internationally. And in 2009, his ideas were endorsed as the “common approach” by 11 United Nations agencies. Mackie is also now involved in a research consortium led by the nonprofit Population Council. The consortium recently won a research grant from the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development – part of a massive campaign that aims to catalyze the global end of FGC, within a generation.

Prevalence of female genital mutilation for women aged 15–49 using UNICEF "The state of the world's children 2015: Executive Summary", November 2014. Credit: from the Wikimedia Commons

Mackie and graduate student research assistants at UC San Diego will be doing both desk and field research on what drives persistence and cessation in different countries. The solution is not likely to be one-size-fits-all, Mackie believes: “Public health models – a single drug for a single bacterium – probably won’t work.” And he is particularly intrigued by Kenya, which has the most spontaneous recession of the practice; perhaps what’s happening there can be harnessed for other nations. The team will also be studying what might be the most cost-efficient ways to help the practice end. While effective, Tostan’s methods are labor-intensive and, by international development standards, quite costly. Building capacity at African universities is part of the project as well.

The research project is currently in its inception phase. In August, Mackie will participate in an orientation of the consortium in Nairobi, where consortium members, most of whom hail from Africa, will train one other. Mackie will teach a course on changing social norms. At the end of five years, Mackie will write a theory of change for ending FGC, outlining a causal path for the desired outcome and describing appropriate measures of success along the way. The details will depend on what’s discovered in different countries in the interim, but the premise will almost certainly stay what it’s been: “Treat people as rational, good people, who want what’s best for their girls.”

Share This:

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.