SPOILER ALERT: Computer Simulations Provide Preview of Next Week’s Eclipse

Predictive Science researchers use SDSC Supercomputer to forecast corona of the sun

Published Date

By:

- Aaron Dubrow

Share This:

Article Content

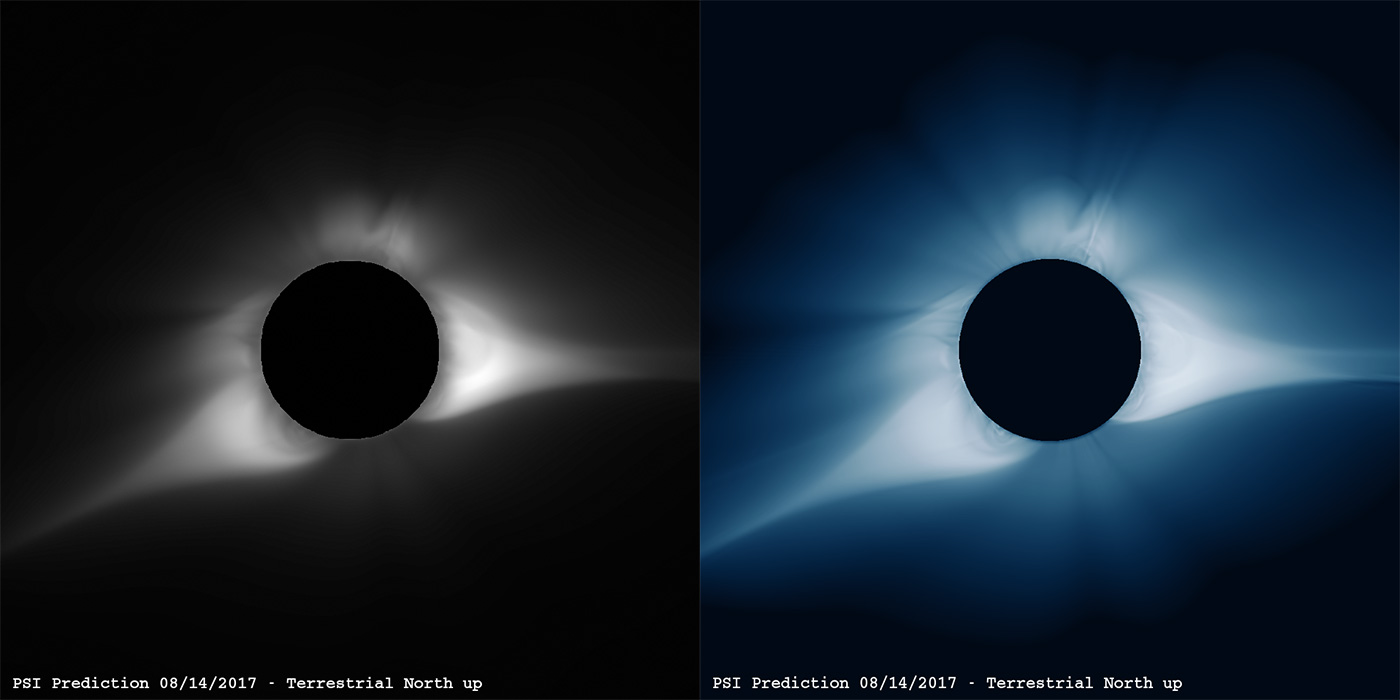

The above images show two versions of the predicted brightness of polarized white light in the corona. The left image shows an image processed to simulate what would be seen when using a "Newkirk" radially graded filter (a method that captures the clearest pictures of the solar corona). The image on the right represents the polarized brightness on a log scale, sharpened using an "Unsharp Mask" filter. The images are aligned to replicate the view of an observer on Earth with a camera pointed toward the Earth's North Pole. Images courtesy of Predictive Science Inc.

On August 21, 2017, a total eclipse of the Sun will be visible across the U.S. The eclipse, which will trace out a 70-mile-wide band across 14 states, is generating excitement and motivating pilgrimages among science enthusiasts nationwide.

Beyond their rarity and surreal nature, solar eclipses help astronomers better understand the Sun – its structure, inner workings and the space weather it generates. They also provide an opportunity for researchers who study solar science to forecast in advance how the Sun will look during the eclipse – proving their predictive chops, so to speak.

A team from Predictive Science Inc. (PSI), based in San Diego, is one such research group. Beginning just weeks ago on July 28, with support from NASA, the Air Force Office of Scientific Research and the National Science Foundation (NSF), researchers began a large-scale simulation of the Sun’s surface in preparation for a prediction of what the solar corona – the aura of plasma that surrounds the sun and extends millions of kilometers into space – will look like during this eclipse.

Using massive supercomputers, including Comet at the San Diego Supercomputer Center (SDSC) at the University of California San Diego, researchers completed a series highly-detailed solar simulations timed to the moment of the eclipse. Researchers also used NASA’s Pleiades supercomputer, as well as Stampede2 at the Texas Advanced Computing Center. Time on Comet and Stampede2 was provided by the NSF’s Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE), a collection of integrated advanced digital resources available to U.S. researchers.

“Advanced computational resources are crucial to developing detailed physical models of the solar corona and solar wind,” said Jon Linker, president and senior research scientist of PSI. “The growth in the power of these resources in recent years has fueled an increase in not only the resolution of these models, but the sophistication of the way the models treat the underlying physical processes as well.”

The team used data collected by the Helioseismic and Magnetic Imager (HMI) aboard NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory, as well as a combination of magnetic field maps, data related to the solar rotation rate, and cutting-edge mathematical models of how magnetohydrodynamics (or the interplay of electrically conducting fluids such as plasmas and powerful magnetic fields) impact the corona.

The research team completed their initial predictions on July 31, 2017, and published their final predictions using newer magnetic field data on their website on August 15, 2017. They will present their results at the Solar Physics Division (SPD) meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS) next week. The simulations are among the largest the research group has performed, using 65 million grid points to provide greater accuracy and realism. The researchers used a magnetohydrodynamic model of the solar corona that included an improved treatment of energy transport.

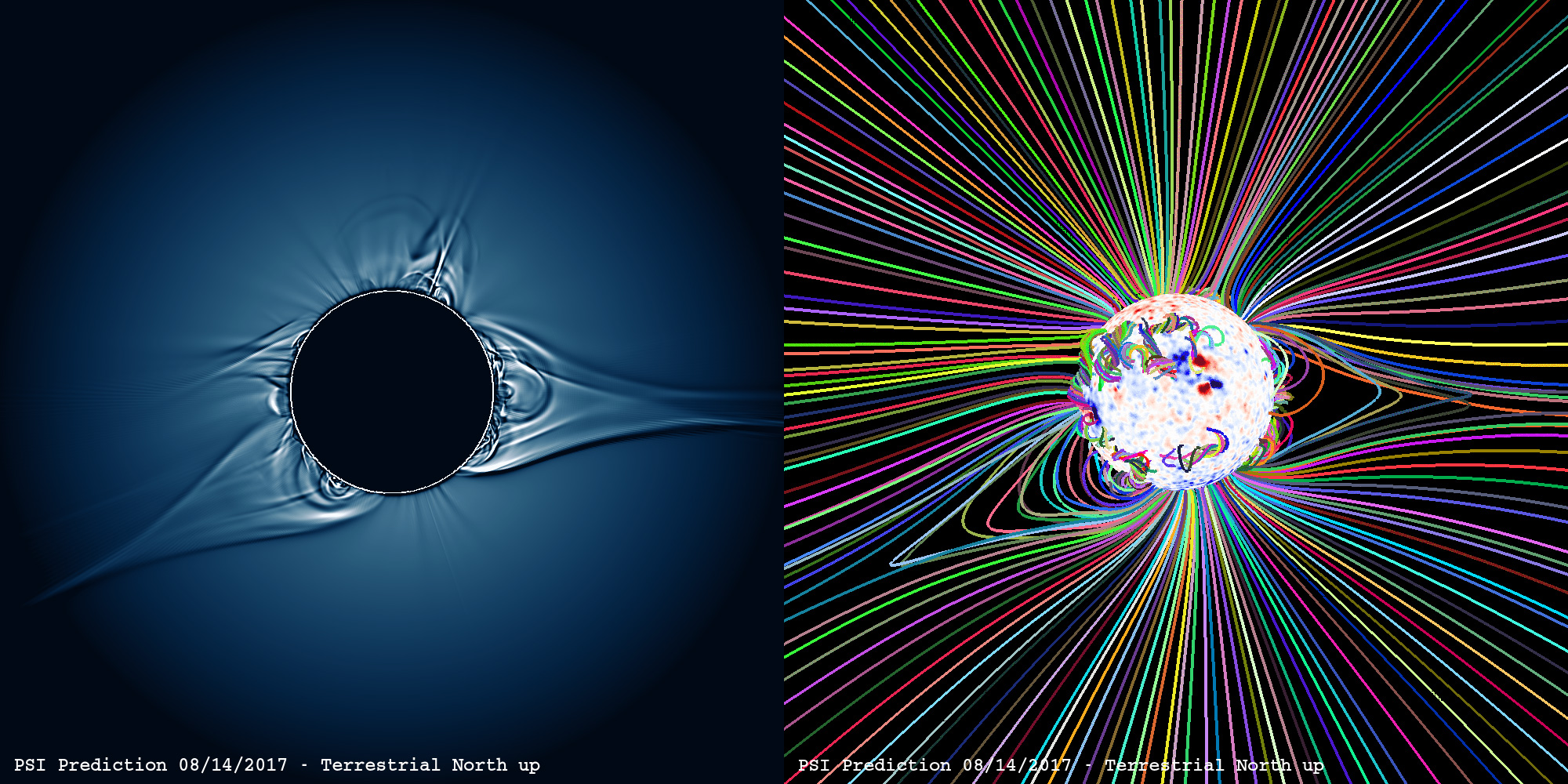

The image the left shows a digital processing of the polarized brightness using a "Wavelet" filter to bring out the details in the image. The image on the right shows traces of selected magnetic field lines from the model. It also shows the intensity of the radial component of the photospheric magnetic field, with the brightest colors showing the location of active regions (strong magnetic fields). Images courtesy of Predictive Science Inc.

While previous predictions in 2006 and 2008 incorporated a more simplistic heating formalism, PSI’s researchers this time applied a wave turbulence-driven methodology to heat the corona. This model better reproduces the underlying physical processes in the corona and has the potential to produce a more accurate eclipse prediction. For the final prediction, they also introduced magnetic shear along polarity inversion lines (lines separating positive and negative polarity regions) where filament channels were observed in extreme ultraviolet emissions by the SDO’s Atmospheric Imaging Assembly instrument. Magnetic shear is a well-known feature of large-scale coronal magnetic fields that has not been accounted for in past predictions.

The introduction of shear qualitatively changes the shape of the streamers and the connectivity of the underlying fields, and increases the free magnetic energy in the corona. One of the team’s simulations even produced a coronal mass ejection (an unusually large release of plasma and magnetic fields from the solar corona) from an active region that will be near the east limb of the Sun on eclipse day – a tantalizing possibility for eclipse watchers.

Visualizing the Surface of the Sun

Once completed, the researchers’ computer simulations were converted into scientific visualizations that approximate what the human eye might see during the solar eclipse.

“The Solar eclipse allows us to see levels of the solar corona not possible even with the most powerful telescopes and spacecraft,” said Niall Gaffney, a former Hubble scientist and director of Data Intensive Computing at the Texas Advanced Computing Center. “It also gives HPC researchers who model high-energy plasmas the unique ability to test our understanding of magneto hydrodynamics at a scale and environment not possible anywhere else.”

Making predictions about the appearance of the corona during an eclipse is a way to test complex, three-dimensional computational models of the sun against visible reality. But the endeavor also has a practical purpose beyond the moments of an eclipse. Accurate predictions of space weather can potentially help authorities prevent the worst impacts of a powerful solar storm, like the one in 1859 — known as the Carrington Event — whose auroras were visible as far south as the Caribbean and which caused telegraphs to short and catch fire.

According to a report by the National Academy of Sciences, if such a storm were to hit the Earth today, it would cause more than $2 trillion in damages. Predicting the arrival of such a solar storm in advance and taking the most critical electronic infrastructure offline could limit its impact. But doing so means understanding how the visible surface of the sun (the corona) relates to the mass ejections of plasma that cause space weather.

Though not an imminent threat, space weather calamities aren’t a fantasy either, according to scientists who don't rule out the possibility for another major impact like the Carrington event. In a widely cited article in Space Weather in 2012, Pete Riley, a senior scientist at PSI, put the odds of such an event occurring by 2020 as 1 in 8. (The US Senate unanimously passed a bill May 2 intended to support space weather research and planning to protect critical infrastructure from solar storms.)

“With the ability to more accurately model solar plasmas, researchers will be able to better predict and reduce the impacts of space weather on key pieces of infrastructure that drive today’s digital world,” Gaffney said.

Interested in seeing the solar eclipse? NSF's National Solar Observatory created an interactive map showing the trajectory of the total eclipse. Find out when it will be visible in your area.

Remember to protect your eyes when viewing the eclipse. LiveScience has a video showing you how to create a DIY solar eclipse viewer.

Share This:

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.