Study Reconsiders Early Evolution of Sea Urchins

Genome-scale analysis of evolutionary relationships and times of origin of sea urchins and their relatives prompts re-evaluation of their fossil record

Published Date

By:

- Robert Monroe

Share This:

Article Content

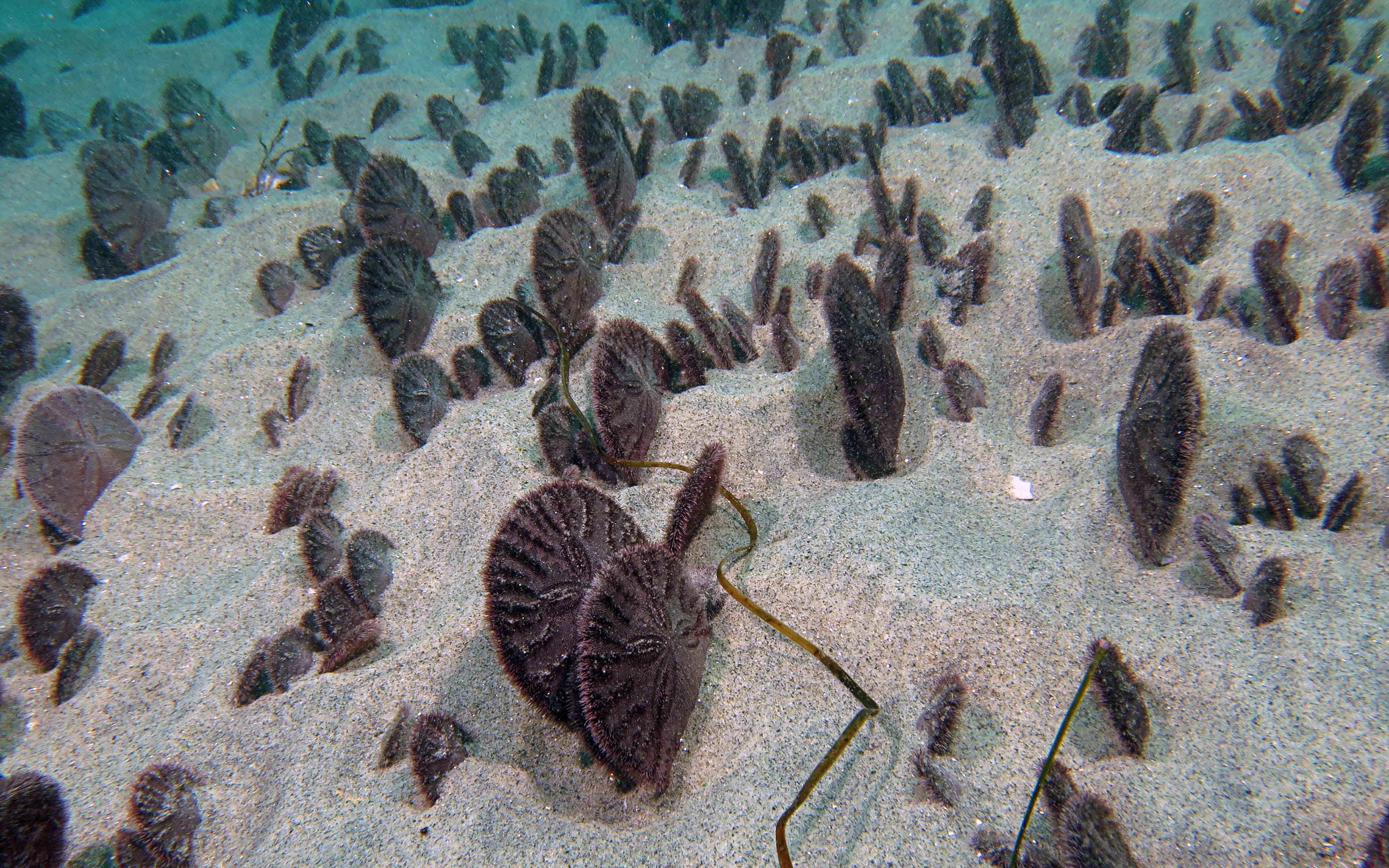

A study led by researchers at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego provides new insight on the origins and early evolution of echinoids, a group of marine animals that includes modern sea urchins, sand dollars, and their relatives.

The work suggests that modern echinoids emerged some 300 million years ago, survived the Permo-Triassic mass extinction event, the most severe biodiversity crisis in Earth’s history, and rapidly diversified in its aftermath. These findings help address a gap in knowledge caused by the relative lack of fossil evidence for this early diversification.

There are more than 1,000 living species of echinoids, including sea urchins, sand dollars and sea biscuits, which live across different ocean environments ranging from shallow waters to abysses. Throughout history, the hard spine-covered skeletons of these creatures have left a large number of fossils. However, despite this remarkable fossil record, their emergence is documented by few fossil specimens with unclear affinities to living groups, making their early history uncertain.

“There are still debates among scientists about when the ancestors of echinoids emerged and what role the mass extinction event that occurred between the Permian and Triassic periods may have played in their evolution,” said first author Nicolás Mongiardino Koch, who completed the work while he was at Yale University, and is now a postdoctoral fellow at Scripps Oceanography.

“We set out to help resolve these debates by combining genomic and paleontological data to disentangle their evolutionary relationships. The extraordinary fossil record of echinoids and the ease with which these fossils can be incorporated in phylogenetic analyses make them an ideal system to explore their early evolution using this approach,” he added.

The study appears today in the journal eLife.

Mongiardino Koch and the team built upon available molecular resources with 18 novel genomic datasets, creating the largest existing molecular matrix for echinoids. Using this dataset, they were able to reconstruct the evolutionary relationships and divergence times of the major lineages of living echinoids and place their diversification within broader evolutionary history. They did so by applying a “molecular clock” technique to their dataset, whereby the rate at which mutations accumulated in the echinoid genomes is translated to geological time with the use of fossil evidence, allowing them to determine when different lineages first diversified.

Their analyses suggest that the ancestors of modern echinoids likely emerged during the Early Permian period and rapidly diversified during the Triassic period in the aftermath of a mass extinction event, even though this event does not seem to have been captured by the fossil record.

Additionally, the results suggest that sand dollars and sea biscuits likely emerged much earlier than thought, during the Cretaceous period about 40 to 50 million years before the first documented fossils of these creatures. The absence of fossils from this critical window of time means that we might lack direct evidence to reconstruct the origin of these unique organisms.

“Our work greatly expands the genomic data available for echinoids and helps resolve some of the long-standing questions around their evolutionary history,” said Scripps marine biologist and study co-author Greg Rouse, whose portion of the work was funded by the National Science Foundation. “Together, the results suggest that we need to re-evaluate the echinoid fossil record, with future studies of overlooked fossil remnants potentially providing further support to our findings.”

Reference specimens housed in the Benthic Invertebrate Collection at Scripps and other collection resources were used in the research. Study co-authors include scientists from the Natural History Museum in London; University College London; the California Academy of Sciences; Queens University, Sussex, United Kingdom; Universidad de Concepcion, Chile; Tel Aviv University; and the Natural History Museum Vienna, Austria.

About eLife

eLife transforms research communication to create a future where a diverse, global community of scientists and researchers produces open and trusted results for the benefit of all. Independent, not-for-profit and supported by funders, we improve the way science is practised and shared. From the research we publish, to the tools we build, to the people we work with, we’ve earned a reputation for quality, integrity and the flexibility to bring about real change. eLife receives financial support and strategic guidance from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, the Max Planck Society and Wellcome. Learn more at https://elifesciences.org/about.

To read the latest Evolutionary Biology research published in eLife, visit https://elifesciences.org/subjects/evolutionary-biology.

Share This:

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.