Study Finds Twist to the Story of the Number Line

Yupno of Papua New Guinea provide clues to the concept’s origins – and suggest familiar notion of time may not be straightforward, either

By:

- Inga Kiderra

Published Date

By:

- Inga Kiderra

Share This:

Article Content

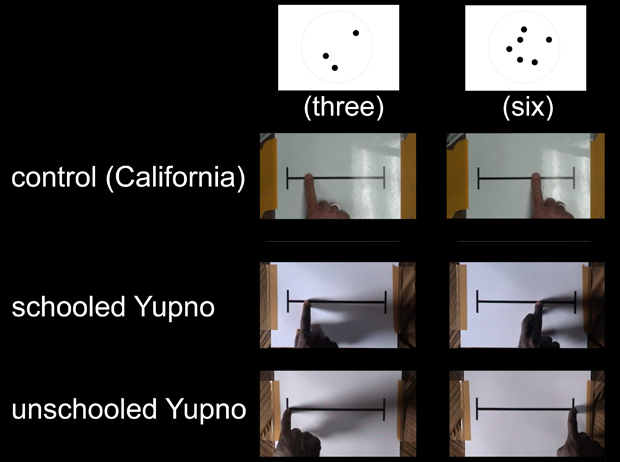

Confirming a Yupno participant’s understanding of numbers. All images courtesy of Embodied Cognition Laboratory, UC San Diego.

Tape measures. Rulers. Graphs. The gas gauge in your car, and the icon on your favorite digital device showing battery power. The number line and its cousins – notations that map numbers onto space and often represent magnitude – are everywhere. Most adults in industrialized societies are so fluent at using the concept, we hardly think about it. We don’t stop to wonder: Is it “natural”? Is it cultural?

Now, challenging a mainstream scholarly position that the number-line concept is innate, a study suggests it is learned.

The Yupno in the studied village are subsistence farmers. Most have little formal schooling. While there is a native system for counting, with precise concepts and words for numbers greater than 20, there doesn’t seem to be any evidence of measurement of any sort.

The study, published in PLoS ONE April 25, is based on experiments with an indigenous group in Papua New Guinea. It was led by Rafael Núñez, director of the Embodied Cognition Lab and associate professor of cognitive science in the UC San Diego Division of Social Sciences.

“Influential scholars have advanced the thesis that many of the building blocks of mathematics are ‘hard-wired’ in the human mind through millions of years of evolution. And a number of different sources of evidence do suggest that humans naturally associate numbers with space,” said Núñez, coauthor of “Where Mathematics Comes From“ and co-director of the newly established Fields Cognitive Science Network at the Fields Institute for Research in Mathematical Sciences.

“Our study shows, for the first time, that the number-line concept is not a ‘universal intuition’ but a particular cultural tool that requires training and education to master,” Núñez said. “Also, we document that precise number concepts can exist independently of linear or other metric-driven spatial representations.”

Núñez and the research team, which includes UC San Diego cognitive science doctoral alumnus Kensy Cooperrider, now at Case Western Reserve University, and Jürg Wassmann, an anthropologist at the University of Heidelberg who has studied the indigenous group for 25 years, traveled to a remote area of the Finisterre Range of Papua New Guinea to conduct the study.

The upper Yupno valley, like much of Papua New Guinea, has no roads. The research team flew in on a four-seat plane and hiked in the rest of the way, armed with solar-powered equipment, since the valley has no electricity.

The indigenous Yupno in this area number some 5,000, spread over many small villages. They are subsistence farmers. Most have little formal schooling, if any at all. While there is no native writing system, there is a native counting system, with precise number concepts and specific words for numbers greater than 20. But there doesn’t seem to be any evidence of measurement of any sort, Núñez said, “not with numbers, or feet or elbows.”

We learn the number line, says UC San Diego cognitive scientist Rafael Núñez: “Mathematics is neither hardwired, nor ‘out there.’”

Neither Hard-Wired nor “Out There”

Núñez and colleagues asked Yupno adults of the village of Gua to complete a task that has been used widely by researchers interested in basic mathematical intuitions and where they come from. In the original task, people are shown a line and are asked to place numbers onto the line according to their size, with “1” going on the left endpoint and “10” (or sometimes “100” or “1000”) going on the right endpoint. Since many in the study group were illiterate, Núñez and colleagues followed previous studies and adapted the task using groups of one to 10 dots, tones and the spoken words instead of written numbers.

After confirming the Yupno participants’ understanding of numbers with piles of oranges, the researchers gave the number-line task to 14 adults with no schooling and six adults with some degree of formal schooling. There was also a control group of participants in California.

The researchers found that unschooled Yupno adults placed numbers on the line (or mapped numbers onto space), but they did it in a categorical manner, using systematically only the endpoints: putting small numbers on the left endpoint and the mid-size and large numbers on the right, ignoring the extension of the line — an essential component of the number-line concept. Schooled Yupno adults used the line’s extension but not quite as evenly as adults in California.

“Mathematics all over the world – from Europe to Asia to the Americas – is largely taught dogmatically, as objective fact, black and white, right/wrong,” Núñez said. “But our work shows that there are meaningful human ideas in math, ingenious solutions and designs that have been mediated by writing and notational devices, like the number line. Perhaps we should think about bringing the human saga to the subject – instead of continuing to treat it romantically, as the ‘universal language’ it’s not. Mathematics is neither hardwired, nor ‘out there.’”

Unschooled Yupno adults used systematically only the endpoints of the number line.

Out-of-Body Time

The researchers ran several experiments while in Gua, Papua New Guinea, including those that examine another fundamental concept: time.

When talking about past, present and future, people all over the world show a tendency to conceive of these notions spatially, Núñez said. The most common spatial pattern is the one found in the English-speaking world, in which people talk about the future as being in front of them and the past behind, encapsulated, for example, in expressions such as the “week ahead” and “way back when.” (In earlier research, Núñez found that the Aymara of the Andes seem to do the reverse, placing the past in front and the future behind.)

In their time study with the Yupno, now in press at the journal Cognition, Núñez and colleagues find that the Yupno don’t use their bodies as reference points for time – but rather their valley’s slope and terrain. Analysis of their gestures suggests they co-locate the present with themselves, as do all previously studied groups. (Picture for a moment how you probably point down at the ground when you talk about “now.”) But, regardless of which way they are facing at the moment, the Yupno point uphill when talking about the future and downhill when talking about the past.

Future is uphill; past is downhill. A participant outdoors produces a backward gesture associated with the Yupno word for “yesterday” when facing uphill (A) and a frontward gesture when facing downhill (B). He produces contrasting, upward gestures associated with “tomorrow” (C, D).

Interestingly and also very unusually, Núñez said, the Yupno seem to think of past and future not as being arranged on a line, such as the familiar “time line” we have in many Western cultures, but as having a three-dimensional bent shape that reflects the valley’s terrain.

“These findings suggest that how we think about abstract concepts is even more flexible than previously thought and is profoundly affected by language, culture and environment,” said Núñez.

“Our familiar notions on ‘fundamental’ concepts such as time and number are so deeply ingrained that they feel natural to us, as though they couldn’t be any other way,” added former graduate student Cooperrider. “When confronted with radically different ways of construing experience, we can no longer take for granted our own. Ultimately, no way is more or less ‘natural’ than the Yupno way.”

The research was supported by a UC San Diego Academic Senate grant, an Institute for Advanced Studies in Berlin fellowship, a UCSD Friends of the International Center fellowship, and the Marsilius Kolleg Heidelberg.

Share This:

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.