UC San Diego Humanities Professors Collaborate to Create New Book about Chinese Film

Published Date

By:

- Dirk Sutro

Share This:

Article Content

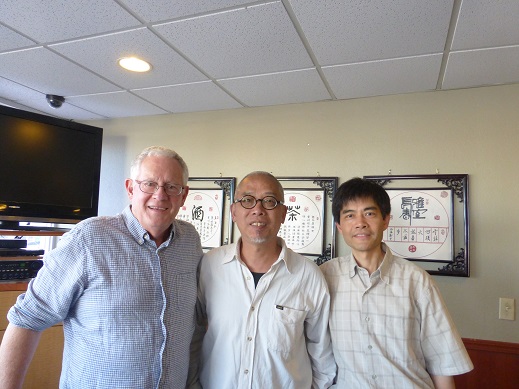

From left to right: Paul Pickowicz, Wu Wenguang and Yingjin Zhang. Photo courtesy of Yingjin Zhang.

The University of California San Diego’s Division of Arts and Humanities is committed to interdisciplinary collaboration. Consistent with that approach, Department of History’s Distinguished Professor Paul Pickowicz and Department of Literature’s Distinguished Professor and Chair Yingjin Zhang have coedited a new book, “Filming the Everyday: Independent Documentaries in Twenty-First Century China” (Rowman & Littlefield, 2017). The publication includes essays about a Chinese film group led by Wu Wenguang, a former artist-in-residence at UC San Diego, who first revealed the struggles of rural people at a time when China’s state-controlled media depicted a thriving, modern country. The book’s debut coincides with Pickowicz’s retirement announcement after more than 40 years. He will deliver a parting lecture entitled, “Very Close Encounters: Modern China at the Grassroots,” from 3-5 p.m. on Jan. 18 at the Faculty Club on campus.

The collaboration is an ideal one considering Pickowicz’s academic focus on history and Zhang’s expertise in comparative literature. Both also share a mutual interest in Chinese film and are involved with Chinese studies at UC San Diego. They co-authored their first book in 2006, and they have since teamed up on projects enjoining their academic interests and shared passions. Their latest book offers a diverse analysis of Wenguang’s “The Memory Project”—an ongoing effort to develop young Chinese filmmakers by sending them out to capture the untold stories and memories of China’s overlooked people. The documentary tells the stories of elderly Chinese survivors of The Great Famine of 1958-1960, when as many as 30-40 million perished. Pickowicz explains that the famine was a product of Mao Zedong’s “Great Leap Forward” modernization campaign, which exploited rural Chinese.

“These filmmakers provided what people outside of China and even inside of China may not be aware of through mainstream media,” Zhang said. “This was a hidden aspect of contemporary Chinese life. Interestingly, what happened was that these young people used their presence in the villages not only to retrieve memories but to engage in some grassroots activism such as helping school children to learn about Chinese history, or to raise money for people in need. Documentary filmmaking became an activist project involving local people.”

The Pickowicz-Zhang book also emerged from a 2014 conference at UC San Diego that the professors co-organized. The conference focused on “The Memory Project” and drew several professors, graduate students and invited scholars in film studies, history, literature, political science, sociology and visual arts. Conference participants viewed 23 documentaries, attended daily forums and held one-on-one meetings with Wenguang, who was a resident artist on campus at the time.

Image of the book cover for Paul Pickowicz’s and Yingjin Zhang’s new book. Photo courtesy of Paul Pickowicz.

Following the conference, scholars submitted essays to Pickowicz and Zhang, who selected several to include in their new book. Angie Chau, who earned a Ph.D. in comparative literature at UC San Diego in 2012, was among the contributors with her essay, “From Root-Searching to Grassroots.”

“I was interested because of my work on the post-’80s generation, the label given to writers and filmmakers born after 1980,” said Chau, who, with Pickowicz’s and Zhang’s encouragement during graduate school, adopted an interdisciplinary research approach that often includes film in her teaching. “Why would these young people want to go back to their ancestral villages, especially since they have been criticized as having no interest in history or politics? My paper explores how this return to the countryside is a very common trope in 20th century Chinese literature, especially in the context of experimental fiction.”

According to Zhang, China’s young people often leave their villages to seek opportunities as a result of urbanization. “They go to the cities to find work and they only return to their villages for holidays, sometimes only once a year,” Zhang said. “Middle-aged people are mostly gone. So you have grandchildren living with grandparents, and the middle generation is missing. That’s pretty scary.”

Because many independent Chinese documentaries present a grittier, sometimes darker, side of China that is at odds with government propaganda, the government has often cracked down on these filmmakers and supporters, explained Zhang. He said they are generally let off with a warning and usually find new ways to circulate the work. In recent years, though, the government has become more aggressive, and once-thriving indie film scenes in Beijing, Nanjing and Kunming have all but disappeared.

“There were many festivals, public screenings and artists’ forums until about a decade ago when, one by one, these were shut down by government officials,” Zhang said. “They no longer have stable venues, but that doesn’t mean underground filmmaking has stopped. It has actually increased. Every year there are 30 to 50 independent productions and many are pretty good.”

Pickowicz and Zhang’s new book, according Pickowicz, is really about cultural studies, broadly defined, and inclusive of history, literature, film and more. “All of us who work in the China studies field are interdisciplinary in our approach. You have to be,” he said.

The history and literature departments at UC San Diego are two of six departments within the No. 23 nationally ranked Division of Arts and Humanities at UC San Diego (U.S. News & World Report’s 2017 Best Global Universities). The other division departments include philosophy, music, theatre and dance, and visual arts.

Share This:

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.