UC San Diego Scientists Investigate Global Hemorrhagic Fever Bacterial Disease

Grant will focus on leptospirosis, which infects millions but is poorly understood and often misdiagnosed

Published Date

By:

- Scott LaFee

Share This:

Article Content

An international research team, headed by Joseph Vinetz, MD, professor of medicine at University of California, San Diego School of Medicine and director of the UC San Diego Center for Tropical Medicine and Travelers Health, has been awarded a 5-year, $1.89 million cooperative agreement to carry out translational research studies of leptospirosis, an infectious and sometimes fatal bacterial disease endemic in much of the world.

Funding comes from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID) under the auspices of the International Collaborations in Tropical Disease Research program.

“Leptospirosis is woefully neglected because it is so difficult to diagnosis,” said Vinetz. “It does not even appear on global lists of neglected tropical diseases despite a case fatality rate as high as 20 percent, with clinical manifestations that can mimic viral hemorrhagic fevers, such as those caused by Ebola virus.”

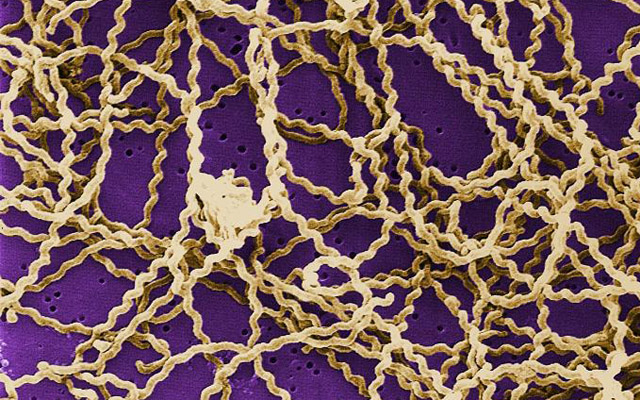

The disease is caused by bacteria of the genus Leptospira, which infect a wide range of animals, domestic and wild, primarily rodents, livestock and dogs. Urine from infected animals, which show no symptoms of the disease, contaminates water and soil, persisting for weeks to months. The bacteria enter humans through contact with skin or mucous membranes. Person-to-person transmission is rare.

Symptoms are numerous, including headache, vomiting and diarrhea, and are often attributed to other ailments. Leptospirosis can be treated with antibiotics, but left untreated it can result in kidney damage, meningitis, liver failure, respiratory distress and death.

Leptospirosis occurs worldwide – it’s an occupational hazard for those working outdoors or with animals – but it is most prevalent in developing countries, particularly urban slum areas with inadequate sewage disposal and water treatment. It’s estimated that 7 to 10 million people are infected annually; the death rate is unknown.

Vinetz and colleagues will focus their research in two countries where leptospirosis is common: Peru and Sri Lanka. (Vinetz also heads a malaria research center based in Peru.) Collaborators include project leaders Suneth Agampodi, MD, at Rajarata University of Sri Lanka, and Jessica Ricaldi, MD, PhD, at Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia in Peru.

The cooperative agreement consists of multiple elements, including:

- Comparative field studies of suspected acute cases of leptospirosis to contrast urban versus rural and seasonal versus perennial risk areas in Peru and Sri Lanka, characterizing patient treatments and outcomes and creating a gold-standard validated specimen bank for testing novel diagnostic test.

- Applying newly biotechnology approaches to develop new diagnostic tests both for individual diagnosis and to estimate the global burden of disease.

“Our goal with this grant is one that has been, at least to this point, insurmountable: Develop a diagnostic test for leptospirosis that is inexpensive, sensitive and efficient, but also easy-to-use and works regardless of the underlying transmission of the disease. Better diagnostic accuracy and efficiency would mean quicker, more appropriate therapy and improved clinical outcomes,” said Vinetz. “We expect to create new tools for diagnosing leptospirosis infections in humans, and do it in a way that leads to the production of a point-of-care diagnostic device that enhances the capabilities of foreign researchers and healthcare providers to grapple with this widespread disease and reduce its mortality.”

Share This:

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.