Vinculin protein boosts function in the aging heart

Published Date

By:

- Deborah Osae-Oppong

Share This:

Article Content

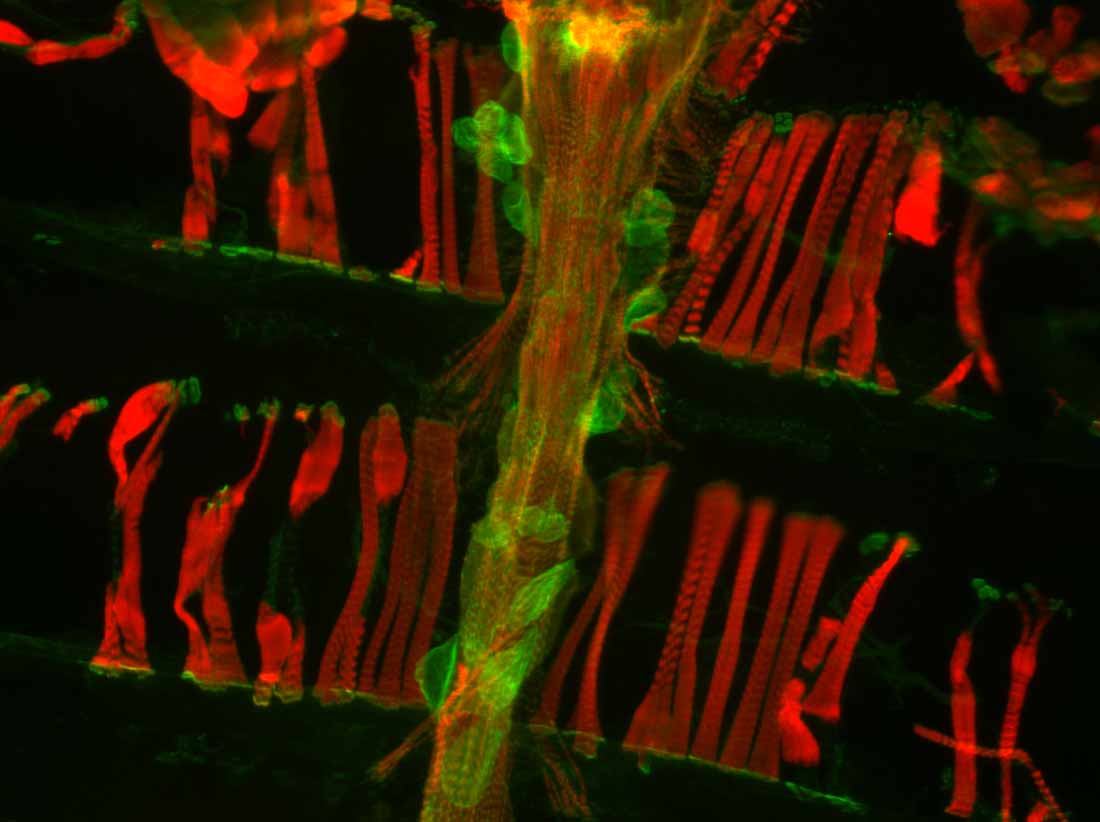

Image of the heart (center) running along the abdomen. Pericardial cells around the heart and abdominal wall muscles in the background can also be seen. Red = Actin (Phalloidin). Green = Vinculin. At this magnification, it's to see vinculin in the muscle cells, but you can see strong labeling of the blobby Pericardial cells. Stain is of a 1 week old female wildtype. Credit: Gaurav Kaushik and Ayla O. Sessions

A team of researchers led by bioengineers at the University of California, San Diego provide new insights on how hearts “stay young” and keep functioning over a lifetime despite the fact that most organisms generate few new heart cells. Identifying key gene expression changes that promote heart function as organisms age could lead to new therapy targets that address age-related heart failure.

The researchers found that the contractile function of the hearts of fruit flies is greatly improved in flies that overexpress the protein vinculin, which also accumulates at higher levels in the hearts of aging rats, monkeys and humans. In addition, flies genetically programmed to express elevated levels of vinculin lived significantly longer than normal fruit flies. The new study attributes the longer life of the flies to the improved contractile function of the heart due to the presence of more vinculin, which helps with the structure of the heart and connects heart muscle cells.

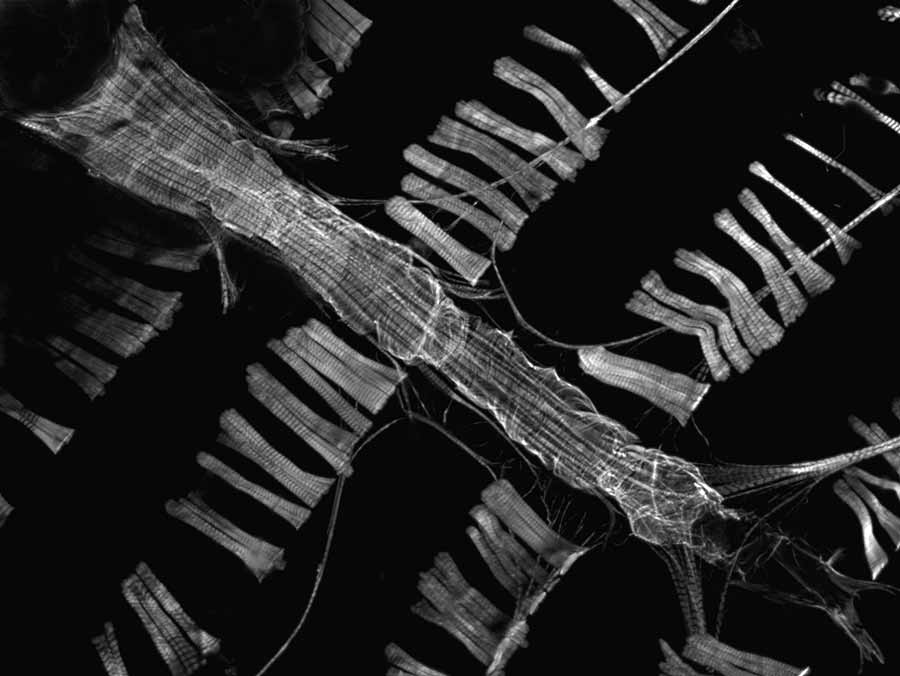

TRITC-Phalloidin labeled wild-type Drosophila heart tube and associated structures (10× magnification). Credit: Anthony Cammarato, Johns Hopkins University

This work is published in the June 17 issue of Science Translational Medicine.

Heart disease is the leading cause of death globally and advanced age is a primary risk factor.

“With the average age being projected to increase dramatically in the coming decades, it is more important than ever that we understand and develop therapies for age-related heart failure,” said Adam Engler, a bioengineering professor at UC San Diego and senior author on the paper. “The results of this study implicate vinculin as a future candidate for therapy for people at risk of age-related heart failure.”

For example, if additional research supports these new findings, targeted gene or drug therapies related to vinculin and its network of proteins could be developed to strengthen the hearts of patients suffering from age-related heart failure.

“More than 80 percent of protein groups found in flies, including vinculin network proteins, are similar to those found in rats and monkeys,” said Gaurav Kaushik, lead author on the study. He worked on this project as a bioengineering Ph.D. student in Engler’s lab at UC San Diego and is now a postdoctoral researcher at Harvard Medical School. “We chose to focus on the proteins that naturally increase in expression in the aging hearts of flies, rats and monkeys. Since deletion or mutation of these proteins can lead to cardiomyopathy in patients, we wondered if their age-related upregulation was beneficial to the heart. Moreover, would overexpressing them improve heart function?”

Kaushik and colleagues genetically modified fruit flies to overexpress proteins, including vinculin.

Remodeling the heart

The human heart is capable of functioning for decades despite the fact that few new heart cells are generated over the course of a lifetime, indicating that alterations in gene expression, known as “remodeling events” help to maintain heart function with age.

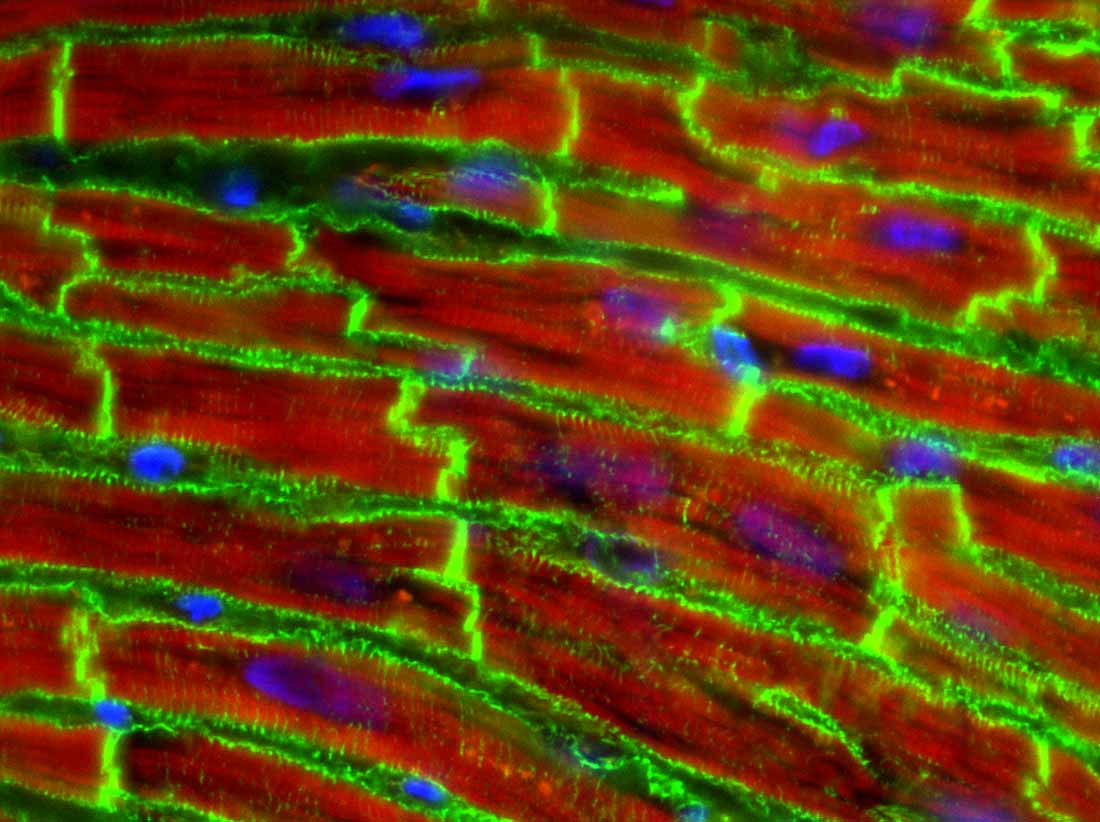

Slice of the left ventricle from an aged (2 year old) female rat. Vinculin (green) strongly labels the points at which muscle cells connect to each other and their microenvironment. Red = Actin (Phalloidin), Blue = Nuclei (DAPI). Credit: Gaurav Kaushik.

“Because renewal of heart cells is limited, maintenance of the heart may depend on remodeling events over time,” said Engler. “Identifying which events are conserved within and between organisms and which result in improved heart function is difficult but could be incredibly valuable.” That’s one of the tasks the researchers set out for themselves. Engler continues, “Within any muscle, the contractile structures become more disordered with age. In heart muscle, vinculin is needed to preserve that structure by holding it together. By performing a kind of open-heart surgery on the flies that overexpressed the protein, we were able to see that the longer life of these flies was due to improved heart muscle function.”

In the study, 50 percent of vinculin-overexpressing flies lived past 11 weeks, to a maximum of 13 weeks. In contrast, 50 percent of control flies only made it to 4 weeks old and none lived past 8 weeks.

“Fruit flies only live for a few weeks which makes them an ideal model for studying aging,” Engler explained.

High school students play a role

Near the beginning of the study, Kaushik and Engler began an outreach effort with a local high school class in San Diego, CA. Kaushik tasked the students with a small pilot study in which they monitored the genetically modified fruit flies over a period of six weeks. Jesse Robinson is a biology teacher at Gary and Jerri-Ann Jacobs High Tech High Charter School. Each year, Robinson’s junior-level biology class works with local scientists on a project.

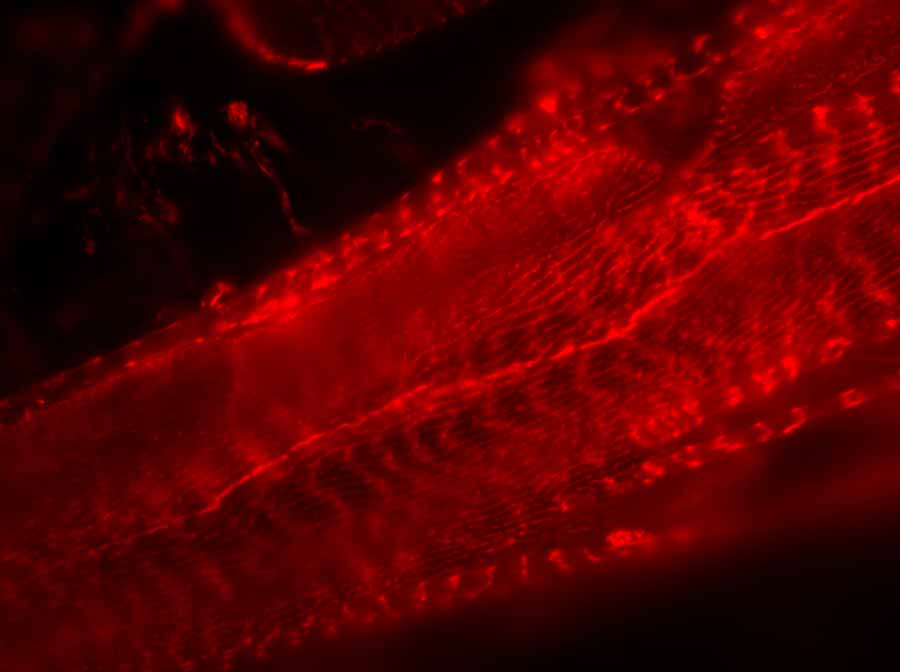

Red: β1D-integrin (an adhesion protein). The image is a stain of a 1 week old female wildtype heart. Credit: Gaurav Kaushik

“Project based learning is part of the philosophy of the school,” said Robinson. “The goal is to immerse students in authentic learning experiences with adult professionals to prepare them for college and career.”

Carl Shefcik, Madison Clark, Hannah Goodwin and Stephen To, now graduating seniors, were all part of Robinson’s class in the Fall of 2013 when the project was assigned.

“We were divided into pairs and assigned two groups of fruit flies – a control group, and a second strain containing one of the mutations that Dr. Engler’s group identified,” said To.

“We didn’t know which group was the control group, and which had the mutation,” recalls Sheficik. “Because of that, we needed to make sure that we kept careful track of which flies died a natural death over a period of six weeks. We found that the group that overexpressed the protein vinculin were outliving the control group by about seven weeks – that’s three times the normal lifespan of a fruit fly!”

The outcome was surprising to Engler and Kaushik, who as a result decided to expand the experiments to focus on vinculin for the study being published in Science Translational Medicine.

“As a teacher, it was neat to see the students tell a story with the data they collected,” said Robinson, who added that this is the first time one of these collaborations was associated with an academic paper. “Dr. Engler was able to ask ‘why’ as a result of the students’ explanation of the data.”

“The project drove my interest in a career in biology,” said Clark, who will attend Cal Poly Pomona in the Fall for biology with an emphasis in microbiology. “It’s really incredible to have participated as a high school student, and even more so to know that the research being done on vinculin could one day change lives. After all, that’s what science is all about.”

Discoveries that change lives increasingly involve engineers.

“Life is complex, and everyone approaches it from a different viewpoint,” said Kaushik. “Engineers may take notice of problems or solutions that a medical doctor may not. We’re needed to accelerate healthcare solutions because we see them with a different set of eyes.”

Share This:

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.