By:

- Mario C. Aguilera

Published Date

By:

- Mario C. Aguilera

Share This:

Photos by Erik Jepsen/UC San Diego Publications

Shatterproof: The Seeds of a Blockbuster Discovery

Solving a game-changing genetic puzzle paves the way for an agricultural revolution that will reach kitchens around the world

In today’s mercurial news cycle, the true value and impact of basic scientific research often gets lost in the shuffle.

Basic science yields discoveries that are crucial to our lives and the world we inhabit, generating advances that enrich our knowledge about life, health and the natural wonders that shape our existence. But in the modern era of instant gratification and razor-thin attention spans, such contributions are too often supplanted by glitzy tweets and bite-sized news nuggets.

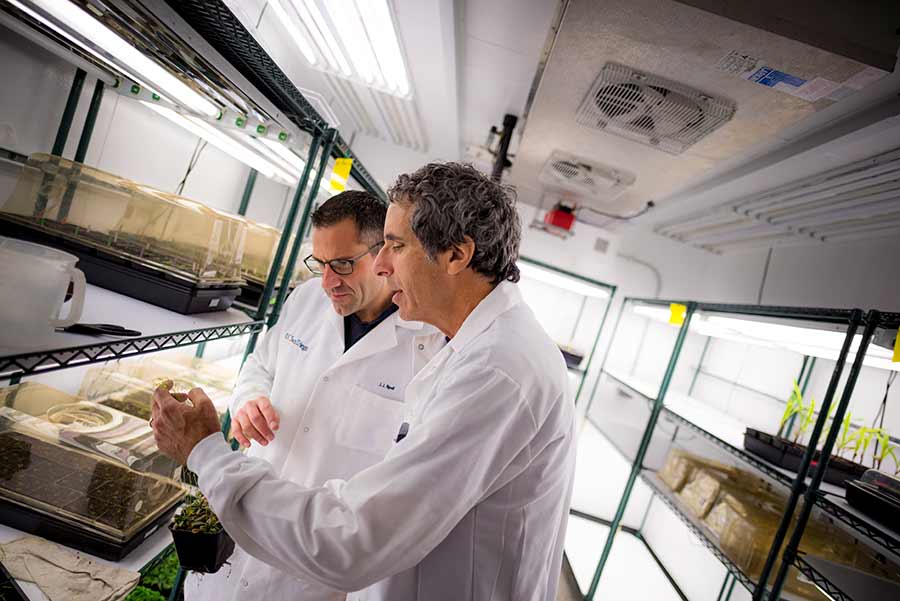

Specialist Juan Jose Ripoll-Samper (left) and Professor Marty Yanofsky study the mechanisms that control fruit and flower development in plants.

Science works on a much different time scale. Years of foundational research could perhaps one day pay off in a breakthrough discovery, whose true ramifications may not be felt until much farther down the road. Such is the case for one groundbreaking UC San Diego discovery currently blossoming across the lush golden splendor of Canada’s canola fields—an innovation whose full reverberations have taken decades to realize.

The discovery traces its roots to the 1990s inside plant biologist Marty Yanofsky’s laboratory on the third floor of UC San Diego’s Muir Biology Building. Today, the full force of the innovation has begun to crest, kick starting a revolution rippling through the multibillion dollar canola industry.

Earth-Shattering Pods

Canadian scientists developed canola (a mash-up of “Canada” and “ola,” meaning “oil” in Gaelic) in the 1970s from rapeseed, a bright yellow flowering member of the cabbage-mustard family. Because of its health benefits—including low saturated fat content—canola oil skyrocketed as a culinary sensation for health-conscious consumers. The canola agricultural sector boomed not only in Canada and the northeastern United States, but in Australia, Europe, New Zealand and China.

Yet even with such success, canola farmers faced a vexing problem: a significant fraction of canola seeds end up on the ground instead of inside harvesters. This problem stems from the fact that canola plants have evolved an elaborate mechanism to disperse their seeds, a process referred to as “pod shattering.” Like peas, canola plants bear their seeds inside protective pods. When ripe, the pods open, dispersing their precious cargo onto the ground before seeds can be harvested. To maximize their harvest yield, farmers would prefer for these seeds to remain inside the pods and on the plant. It is not uncommon for pod shattering to cause farmers to lose more than half of their crop. Weather events including hailstorms, as one example, can devastate entire crops.

Farmers go to great lengths to minimize the risk of losing their crop, including harvesting far too early. Yet doing so is financially inefficient since immature seeds will fail to produce as much of the coveted canola oil within them compared with fully matured seeds.

When Yanofsky learned of this conundrum, it became clear that this was a basic science challenge ready to be met head on. His laboratory had deep experience studying a close relative of canola called Arabidopsis, a plant that had been adopted as a “model system” by plant biology laboratories around the world.

“The advantage of working in a model system like Arabidopsis is that the tools have already been developed that allow for rapid advances to be made,” said Yanofsky. His group had been using Arabidopsis to identify the major genes that control fruit development. If his group could identify the genes that control fruit opening in Arabidopsis, he reasoned, then they should be able to solve the pod shattering problem in canola.

Rising to The Challenge

Identifying the genes that control fruit opening in Arabidopsis was a painstaking process that took years to bring to fruition, beginning in the early 1990s. Eventually it paid off.

“The end result was very satisfying,” says Yanofsky, who shares credit for the discovery with Sarah Liljegren, Sherry Kempin and Cristina Ferrandiz, three stellar scientists in his lab at the time. “We were able to put together a rather simple model that explains how these genes control the fruit-opening process.”

After patenting their discovery, next came the vexing pod shattering problem in canola.

His group began collaborating with Bayer CropScience, one of the world’s largest biotechnologies companies, which produces and sells canola seeds. This fruitful collaboration allowed them to demonstrate that the very same genes that Yanofsky’s group had discovered could be used to prevent pod opening in canola plants.

Lush canola fields spread across the prairies of Canada.

“At that point, I was convinced that we had solved the pod shattering problem. It was a no brainer,” Yanofsky said. Years of subsequent work by a team of researchers at Bayer finally brought the project to completion. Yanofsky is quick to give ample credit to the talented Bayer team. “Without their persistence, this technology may have never seen the light of day,” he said.

Bayer began rolling out the first pod-shatter resistant canola plants in 2015 and farmers have been ecstatic. Many are calling it a game-changing technology because it completely transforms the way canola is harvested.

Looking back, Yanofsky considers his contribution to solving the vexing canola pod shattering problem to be the most impactful discovery of his research career, which started with a biology degree from UC San Diego in 1978. The discovery certainly has been a boon to Bayer CropScience, which now markets the discovery under the “PodGuard” technology moniker (BASF has since acquired the canola assets from Bayer).

“The podshatter trait that is based on the genes discovered at UC San Diego has proven to be a real life-changer for canola farmers,” said Benjamin Laga, a lead scientist with Bayer who helped commercialize the product. “For me as scientist, reading farmers’ tweets on how podshatter has genuinely impacted their life, that’s pure job satisfaction.”

The company is rolling out new varieties of PodGuard to meet the field conditions of canola-farming regions across Canada, Australia and elsewhere.

“Basic scientific research is critical to our future, since it sets the stage for breakthroughs that will cure human disease and feed our planet’s growing population,” said Kit Pogliano, Dean of the Division of Biological Sciences. “Marty Yanofsky’s shatterproof seed discovery took years to unravel and to develop an application, and it is a wonderful example of how basic research can have a global impact and improve lives around the world.”

Marty Yanofsky, a distinguished professor, UC San Diego alum and the Paul D. Saltman Chair in Science Education, considers his contribution to solving the canola pod shattering problem to be the most impactful discovery of his research career.

“This is another example of the vast research talent and expertise that resides at UC San Diego, and the impact that this research has on the lives of people in our community,” said Paul Roben, associate vice chancellor for Innovation and Commercialization at UC San Diego. “Through programs like Dr. Yanofsky’s, UC San Diego has become a global innovation leader as the top public university nationally for industry partnerships.”

Beyond the economics of giving farmers the ability to maximize their canola yield, a transformational boost to a sector that employs more than 250,000 in Canada and reaches kitchen counters around the world, Yanofsky’s breakthrough has become an environmentally friendly solution.

“Since this technology can dramatically increase seed yield, farmers can get the same yield on less land, meaning fewer chemical pesticides, fertilizers and less water,” said Yanofsky, who looks with satisfaction on the achievement as an excellent example of scientific delayed gratification. “Many discoveries are made in the lab and you think they could have an impact, but never see the light of day. This one emphasizes how basic scientific research can have a profound impact—in fact, in this case, revolutionizing canola agriculture.”

Share This:

You May Also Like

Stay in the Know

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.